Whole of Government Approach to Conflict

R4 Question #2: How could DoD and DoS be better postured to address regional and world conflicts to ensure a whole of government approach to identify and synchronize lines of effort in both planning and execution?

Author | Editor: Canna, S. (NSI, Inc).

Executive Summary

Not many experts were willing to tackle this problem of synchronizing whole of government planning and execution processes across the Department of Defense (DoD) and the Department of State (DoS). While there seems to be a growing acceptance that greater cooperation between DoD and DoS is essential for responding to adversaries that act like complex adaptive systems, no single governmental organ which can, through its own effort, ensure that institutionalized planning and execution cooperation occurs regularly.

n other words, there is no single individual or agency that knows how to implement a whole of government approach or that has the authority to do so, even just between the DoD and DoS, which is a fundamental problem (Serwer). Despite the promising observation that DoD and DoS are “more in alignment than anytime in the last 20 years” (Serwer), some experts passionately concluded that whole- of-government “is an empty slogan and a cruel joke” (Chow).

Both assertions are an accurate and problematic portrayal of the status quo.

This paper outlines some of the challenges facing DoD and DoS Synchronizations as well as some recommendations for what the DoD can do within its current authorities. Bureaucracies resist change, so, ultimately; our contributors suggested two additional recommendations that lie outside DoD jurisdiction and would need to be implemented out by senior US policy makers.

Obstacles to DoD and DoS Synchronization

Focusing solely here on DoD and DoS synchronization—and leaving a true whole of government approaches for another time—, the contributors list five challenges preventing closer collaboration.

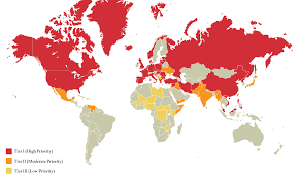

- Giant Imbalance in Capacity: The biggest challenge, for which there are many causes, is the “giant imbalance in capacity” between DoS and DoD (Chow, Serwer). In recent history, the US military instruments of power have been much more powerful than the civilian ones (Serwer).

- Decreased Funding for State: The State Department budget is a fraction of the Defense budget. Serwer notes this imbalance is about to get worse as proposed budget cuts would take more funding away from DoS and increase funding for DoD (see also Chow).

- DoD Called Upon Too Late: The DoD often does not get called in until a crisis has already developed (Chow). Waiting to collaborate with DoS until an active conflict threatens makes it even more difficult to work with DoS given the lack of communication, trust, and training between the two organizations.

- Operational Differences: DoS resists formal plans for its operations (Serwer), given that due to resource constraints, human resource assets are often involved in multiple lines of effort with dynamic prioritization. This approach creates difficulties for synchronization with the DoD, which has the resources for formal planning with specific human resource assets devoted to executing those plans. DoD, as a result, often finds it difficult to know when or how to reach out for assistance and collaboration.

What Can the DoD Do?

Building off the last point, the DoD does not have the ability to fashion a whole of government framework on its own, but contributors note places where DoD can take the lead to start bridging the divide between the two organizations. They suggest two ways forward.

Option 1: Training

Serwer noted that shared DoS/DoD training would go a long way to building mutual trust, esteem, and communication between the two organizations. However, he believes this is nearly impossible in today’s environment. The best he feels the organizations can hope for is some commonality in training material.

Option 2: Start by Cooperating on One Issue: Science Diplomacy/Smart Power

Moloney and Dehgan suggest that DoD and DoS begin working together on an issue of mutual concern: water security. History has shown us that water insecurity is a major driver of conflict, particularly in the Middle East. In particular, Iran is increasingly feeling the pressures of water insecurity, which is could be potentially destabilizing to the country and the region, perhaps compelling it to act in ways unfavorable to US interests. Creating a mutual understanding of the problem and building a plan together to address it could act as a confidence building measure between the two organizations.

Option 3: Reach Out to Experts Outside the DoD

Breslin Smith notes the “national security community faces a unique hurdle in gathering insights in these areas from the academic community,” particularly from Middle East scholars. Breslin Smith notes that policy suffers as a consequence from this divide. Happily, as the successful partnership between USCENTCOM and SMA has shown over the last several months, the DoD is taking steps to reach out to experts than can provide a deep understanding of our partners and adversaries. Over 190 experts have contributed to this effort to date and there are other organizations that also bring DoD and outside experts together.

What Has to Be Done by Policy Makers?

Option 4: Combine National Defense and International Affairs Budget Functions

Breslin Smith suggests combining the National Defense (050) and International Affairs (150) budget functions to get a comprehensive understanding of how National Security funds are allocated. This was last attempted during the Reagan administration. Combining budget functions would allow one to compare all “strategic communication” or “public diplomacy” being done across the DoD and DoS. This would “help the ‘whole of government’ idea, save redundancy, and better focus our efforts,” Breslin Smith argues. This might also help minimize the funding imbalance between DoS and DoD.

Option 5: Develop a Grand Strategy

Coordination is more effective when everyone is moving in the same general direction. The first step is to understand the deep cultural, historical, economic, and political knowledge related to an issue or region of concern (Breslin Smith). The second step is to develop a strategy for addressing the issue. Strategy will not be effective with deep understanding. Only after these first two steps have been accomplished can we design a national security architecture to execute that strategy. Breslin Smith suggested convening a competitive strategy study for addressing challenges facing the USG in the Middle East along the lines of Project Solarium, which was conducted by the National War College for President Eisenhower in response to emerging threats from the Soviet Union.

Contributors

Edward Chow (CSIS), Alex Dehgan (Conservation X Labs), Laura Jean Palmer-Moloney (Visual Teaching Technologies, LLC), Daniel Serwer (Johns Hopkins School of International Studies), Janet Breslin Smith (Crosswinds International Consulting)

Comments