What Extent is Iraqi Army Apolitical

Question (R4.3): To what extent is the Iraqi Army apolitical? Do they have a political agenda or another desired end- state within Iraq? Could the Iraqi military be an effective catalyst for reconciliation between different groups in Iraqi society? Could conscription be an accelerant for reconciliation and if so how could it be implemented?

Author | Editor: Astorino-Courtois, A. (NSI, Inc.).

Executive Summary

The subject of this report touches on a critical issue for the future of Iraq as a unified and stable state: To what degree will the Iraqi Armed Forces be able to serve as the vanguard for resurrection of national identity and tolerance? If the answer is not at all, Iraq as a single independent state is likely doomed.

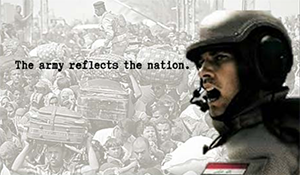

To address the question posed, many of the expert contributors to this Reach-back report begin with an important observation: the Iraqi Army, like other public institutions around the world, is not a unitary actor with a single political orientation, agenda, or desired end- state. Like other militaries, it mirrors the social conditions and pressures of the population from which it comes. For the Iraqi Army, this means the ethno-sectarian divisions, pervasive corruption, and well-ensconced patronage and power networks that work around and despite military rank or process.

How did the Iraqi Armed Forces get to this point?

A number of the contributors point to the turbulent history of the Iraqi Armed Forces (IAF) as the foundation of its current condition. Hala Abdulla of the Marine Corps University dates the beginning of the deterioration of its professionalism and strength to the Saddam Hussein era, when Saddam assassinated senior leaders that he perceived as threats to his control. Over time, this practice meant that the cohort of professional leaders who might have enjoyed broad popular and military regard had been decimated. The 2003 invasion of Iraq by Coalition forces continued the weakening of the Army as an institution. Importantly, that invasion also had the critical effect of drastically changing the sectarian make-up of the Army leadership from Sunni to Shi’a- dominated; a process that was accelerated under the leadership of Nouri al Malaki. Abdulla argues that the post-2003 Army was weaker than the pre-2003 Army reflecting the fragmentation of society, along with rampant corruption and nepotism.

Does the Army have a political agenda? Not exactly.

The contributors to this report each argue that the Iraqi Army is far from apolitical, but importantly, that this fact is the result of the Army’s demographics rather than its partisanship. Dr. Elie Abouaoun of the US Institute of Peace cautions that we take care in thinking of the Army as a “monolith” with a single set of political views. It is because the force is overwhelmingly Shi’a that it naturally reflects the political and social concerns of the Shi’a-led government and communities.

The experts also agree that the Army does not have its own political agenda or cohesive image of the future of the Army or Iraq. Rather than any political orientation in fact, Middle East scholar Shalini Venturelli’s (American University) research identifies the strongest guiding principle in the Army as preservation of individual and group power and influence. This is done in the Army via the same types of social and familial patronage and influence networks found in the rest of the country. It is this urge and the dynamics of competing hidden power networks within the Army that has stymied its re-professionalization and accounts for the corruption and nepotism with which it is plagued.

Could the Army or Special Forces serve as a force for national reconciliation? No way, unless …

There is wide agreement among the authors regarding the prospect that the Iraqi Army could be a catalyst for national reconciliation: they are dubious at best. Wayne White of the Middle East Institute points out that, in its current guise, the “largely Shi’a force sometimes [has been] in league with abusive militias” and, though the Iraqi Army that fought Iran was more than half Shi’a, the years of ethno-sectarian conflict have embittered many in the Army against Sunni, Turkoman, Kurdish, and other groups. Elie Abouaoun (USIP) explains that “solidarity” among some military units might develop, but “the institutional bonding is not strong enough to overcome the vertical divisions along ethnic and sectarian lines.”

The two areas where the experts disagree are: 1) whether the Army’s successful performance in Mosul has rehabilitated its reputation among minority populations; and relatedly, 2) the degree to which the US-trained Iraqi Special Forces (Golden Divisions) that make up a large part of the Mosul force might serve as a model for professionalizing the larger force and catalyzing national regard for the military. Bilal Wahab (Washington Institute for Near East Policy) and Muhanad Seloom (ICSS, UK) believe that the “highly professionalized” Special Forces have “boosted a sense of nationalism” in Iraq and have significantly improved popular perception of forces that not too long ago were seen not as Golden, but as the “Dirty Division.” Yerevan Saeed (Arab Gulf States Institute) and Macin Styszynski (Mickiewicz University, Poland) observe little change in Sunni or Kurdish views of the Iraqi Army, primarily they argue, because these populations observe little change in the Army—which looks very much like the organization until very recently responsible for “widespread abuse, violence and human rights abuses.” Shalini Venturelli (American University) believes that even if there was improved popular regard for the Special Forces, the exceptionalism of the Golden Division is overstated, and that withdrawal of US trainers and support elements would rapidly show these units to be bound by the same corruption and competing power networks as the larger force.

Although highly skeptical of these occurring any time soon, the experts do offer conditions under which the Iraqi Army might eventually serve as an engine of national reconciliation. The most critical of these is (re)gaining popular trust in both the Government of Iraq and the military that serves it. The only way to overcome popular perception of the Army’s Shi’a favoritism is through sincere political reform in which “Sunnis have a major strategic stake” and are convinced of the government’s “enduring commitment to their security regardless of which party(ies) hold the reins of power” (Shalini Venturelli, American U.) Even if there were to be a professionalized, unified Iraqi Army some time in the future, Zana Gulmohamad of Sheffield University forecasts that “the reconciliation will be partial, and not include the entire country,” but instead be limited to Iraqi Arabs (Shi’a and Sunni). The Kurds, he argues, have their own security forces that they will always trust more than the Iraqi Army.

Is conscription a good idea? Not likely.

None of the expert contributors to this report sees conscription into the Iraqi military as a viable path to reconciliation. In fact, some suggest under current conditions military conscription could very easily deepen rather than reduce the ethno-sectarian tensions that wrack the country. While he allows that, “enrolling in the army—including conscription—might ease up inter-personal relations somehow,” Elie Abouaoun contends that the effect does not scale because Sunni “collective fears” of the Army remain. He points to Lebanon’s experience with using compulsory military conscription to encourage national identity among its warring sectarian groups. The failure to enact political reforms, he says, was a major cause of the lackluster results: “failing to embrace an inclusive governance model undermined the possible—though highly unlikely— impact of such efforts. Iraq is not different, especially with the presence of tens of thousands of fighters now enrolled in militias.”3 Again, the military reflects the nation.

The point is this: prior political reform and social integration are not just important facilitators for development and professionalization of the Army and thus its value as a platform for national identity and reconciliation—they are required pre-conditions. Neither the current Government of Iraq nor the Army is likely to succeed in stabilizing the country until Sunni Arabs and other minority populations are integrated into the state’s political, security and social institutions. As Wayne White of the Middle East Institute cautions, if this is ignored, Sunni resistance will persist. Finally, Shalini Venturelli reminds us that, even if these reforms have been made, restoring the trust of Sunnis, Kurds, and other minority groups in the national Army is a decades-long process.

Contributing Authors

Hala Abdulla (Marine Corps University); Dr. Elie Abouaoun (US Institute of Peace); Dr. Scott Atran (ARTIS Research); Zana Gulmohamad (University of Sheffield, UK); Yerevan Saeed (Arab Gulf States Institute); Dr. Muhanad Seloom (Iraqi Centre for Strategic Studies, ICSS, UK); Dr. Marcin Styszynski (Adam Mickiewicz University, Poland); Dr. Shalini Venturelli (American University); Dr. Bilal Wahab (Washington Institute for Near East Policy); Wayne White (Middle East Institute)

Comments