Gray Zone Deterrence: What It Is and How (Not) to Do It

Gray Zone Deterrence: What It Is and How (Not) to Do It.

Author | Editor: Stevenson, J. (NSI, Inc.).

Overview

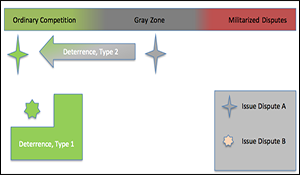

In recent years, state actors, especially but not limited to Russia and China, have increasingly engaged in what the US Government has labeled “gray zone challenges.”1 These are actions that disrupt regional stability and potentially threaten US interests, yet purposefully avoid triggering direct responses (Bragg, 2016). In earlier NSI Gray Zone Concept Papers, we argued that both malicious intent as well as violation of international norms for what is considered “ordinary competition” among states were integral aspects of gray zone challenges. This paper expands this discussion to explore what deterrence would look like in the Gray Zone, and how deterrence operates when ambiguity regarding appropriate response is added to the uncertainties that more typically characterize deterrence decisions. We argue that deterrence in the Gray Zone involves both preventing escalation to direct military conflict and assuaging an actor’s desire to violate international norms of behavior.

Foundations: Thinking through Classic Deterrence Theory

In the classic model of deterrence, a state seeking to deter should credibly threaten to impose negative consequences on a target if the same target does not comply with the action-avoidance request. Similarly, the target must be credibly assured that the deterring state will not impose harmful consequences if it refrains from taking the action.

- A state credibly threatens a target with negative consequences if the target state takes a certain action or violates a prohibition.

- The deterring state credibly assures its target that no negative consequences will follow if compliance is achieved.

- The targeted state refrains from taking the prohibited specific activities.

Academically, classic deterrence theory emerged to explain what to do about the conventional and nuclear force postures of the Soviet Union—a peer competitor that pursued a fundamentally different logic of political and economic order. The United States and the Soviet Union were in a situation of balanced power, and conceptions of deterrence derived in this setting reflected this structure.

Clearly this balanced structure no longer applies. The United States leads the world in military research and development, and enjoys one of the few long-distance power projective capabilities in the world. Moreover, the United States participates in almost every critical security institution (e.g., NATO), helped design the post-war economic institutions (e.g., GATT/WTO, IMF), and possesses military bases on every continent and near every major region of operation (Johnson, 2007; Gilpin, 2001). Our closest near competitors are states like Russia and China, which while opposed to many of the foreign policy choices of the United States and its allies, seek a larger voice in the current order, rather than a fundamentally different logic of political and economic order (Pagano, 2017).

It stands to reason that the principles of deterrence that worked best to contain the Soviet Union may differ from the principles of deterrence that work best to constrain the more limited ambitions of modern Russia and China, competitors of much lesser capability. Classic deterrence principles also seem limited in providing insight into the conditions under which we are likely to deter non-state actors (or even what deterrence of non-state actors looks like). Many approaches to countering violent non-state mobilization call for the destruction or complete dismantling of the non-state organization. Classic deterrence theory suggests that under these conditions the groups targeted would be “undeterrable,” as there is not likely the level of imposed costs that would get these group to change their behaviors.

Comments