Counter and Delegitimize Violent Extremism

Defining a Strategic Campaign for Working with Partners to Counter and Delegitimize Violent Extremism Workshop.

Author | Editor: Arana, A., Baker, T. & Canna, S. (NSI, Inc).

Dr. Hriar Cabayan, OSD, welcomed the participants on behalf of the Department of Defense (DoD), the State Department (DoS), and the RAND Corporation to the Defining a Strategic Campaign for Working with Partners to Counter and Delegitimize Violent Extremism workshop held from 19-20 May 2010 at Gallup World Headquarters in Washington, DC. The workshop focused on strategic communications and violent extremism and was designed to inform decision makers and was not intended as a forum for policy discussion. The workshop emerged from an SMA- and AFRL-sponsored white paper entitled Protecting the Homeland from International and Domestic Terrorism for Counter-radicalization and Disengagement. As the white paper was being written, it came to Dr Cabayan’s attention that Dr. Paul Davis at the RAND Corporation was writing an integrative literature review on the subject. The RAND report was entitled Simple Models to Explore Deterrence and More General Influence in the War with Al-Qaeda. Building on that, CAPT Wayne Porter wrote a paper on the strategic campaign to counter and delegitimize violent extremism, which resulted in the genesis of this workshop.

The workshop was organized as a series of panel discussions and individual discussion sessions. This executive summary is organized by session for ease of reading and use.

Opening Remarks: Pradeep Ramamurthy

Pradeep Ramamurthy, Senior Director for Global Engagement on the White House’s National Security Council (NSC), began the conference with a discussion of how the current Administration defines countering violent extremisms (CVE) and strategic communications. He then provided an overview of key communication and engagement goals and objectives, highlighting that CVE was one of the Administration’s many priorities. Mr. Ramamurthy then provided an outline of critical elements of strategic communications that should stay in participants’ minds for the duration of the conference; noting (1) the importance of coordinating words and actions that involves an all-of- government approach; (2) the need to do a better job of coordinating multiple messaging efforts across agencies; and, (3) listening and engaging with target communities on topics of mutual interest, not just terrorism. He sought to emphasize that the conference served as an invaluable launching point for government introspection and the injection of new ideas from outside experts.

Session 1: Trajectories of Terrorism

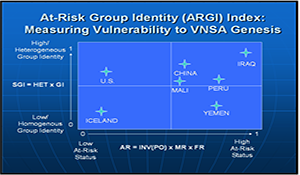

Dr. Laurie Fenstermacher, AFRL, and Dr. Paul Davis, RAND Corporation, moderated the first session of the day on the causes and trajectories of terrorism from perceived socio-economic and political grievances to recruitment and mobilization. The participants, who included representatives from government, industry, and academia, spoke on a variety of related issues including the dynamics and tactics of violent non-state actor (VNSA) communications and decision-making, the role and importance of ideology, and the key causes of popular support for terrorism and insurgencies. The panelists reinforced the need for tailored strategies for individuals based on their motivation (e.g., ideology, self-interest, fear) or based on other factors (e.g., Type 1 or 2 radicals, fence sitters)such as the need to focus on “pull” factors (recruiting, compelling narratives/messages) versus “push” factors and the need to understand ideology and associated terms. Also asserted was the need to target strategies towards the function of ideology (e.g., naturalization, obscuration, universalization and structuring) with culturally and generationally sensitive strategies, which are not based on inappropriate generalizations of past strategies, groups, or movements. Finally, the panel stated that some models need to be changed if they are to be truly useful in understanding terrorism (e.g., rational actor models may need to include altruism). This first panel (taken together with the reference materials) provided a snapshot of the current understanding of terrorism from the perspective of social science. As the first session of the conference, the panel discussion served to provide a common understanding and foundation for the remainder of the workshop.

Working Lunch: An All-of-Government Approach to Countering Violent Extremism: The Value of Interagency Planning

Two representatives of the National Counter Terrorism Center (NCTC) and another representative of the USG outlined the key components of an All-of-Government approach to countering extremism. The NCTC coordinates the efforts of various agencies like the Department of Homeland Security and the FBI on issues of counterterrorism; consequently, they have significant experience in the domestic context. The critical element of the NCTC approach is the importance of “going local” or structuring interventions and responses within the context of a given community, thereby recognizing the inherently local nature of the radicalization process. The NCTC representatives noted the critical importance of getting outside the Beltway and implementing micro-strategies. An unattributed speaker then spoke about the importance of understanding the language that the United States uses to deal with violent extremists and the danger of using the language and the narrative of violent extremism because it only perpetuates their message to the rest of the world. The USG needs to do a better job of communicating its objectives and working with communities to develop solutions to deal with extremist violence. Partnerships with communities have been important tools in helping to address issues of violence, such as gangs, and can be a valuable resource to address the issue of extremist violence. Ensuring that US actions and words are synchronized, and not in contradiction to each other, is critical. As a federal government, the United States must work hard to better understand the complexity of extremist violence by working with state and local authorities, academics, and communities.

Session 2: Whether Violent Islamists Groups Can, in Fact, be Delegitimized?

The panelists of Session 2 were somewhat divided on whether delegitimizing extremists should be approached from a religious perspective or if efforts should be focused on eliminating or minimizing contributing factors. Some participants emphasized the importance of making use of the religious jargon and institutions (like Fatwas) to marginalize the leaders and participants in violent extremists in the eyes of their broader religious communities; indeed, one panelist recommended changing the underlying Quranic hermeneutics to recognize the historical nature of the Quran. Other panelists were wary of labeling extremism as a religious problem, because radicalization and extremism are not new developments in the Middle East; it existed during the nationalist campaigns of the 1960s much as it does today. Almost universally, panelists acknowledged that the West needs to do a better job of selling its own message of what it is that it stands for and what it tries to do in the international community.

Session 3: Strategic Campaign to Diminish Radical Islamist Threats

Session 3, moderated by CAPT Wayne Porter and Special Representative to Muslim Communities Farah Pandith, focused on several features of an effective campaign to combat radicalization. However, there was major contention regarding the degree to which the United States should focus on its own views and reputation versus focusing on supporting other groups or focusing on strategic communication in terms of other countries. Nonetheless, the session reached consensus on several major points including supporting historical traditions and customs of indigenous Muslim cultures and closing the say/do gap to increase consistency. This consistency will lead to credibility, which is critical in conjunction with whether the message is compelling and whether it connects with the audience. It was also considered important to align government, private sector, and Muslim leaders to forge strategic alliances. This empowerment of many voices creates competition for radicals attempting to monopolize communications to these populations and allows the United States to partner with and support potential leaders. Such an empowerment strategy also allows the United States to implement a wide variety of approaches and employ diagnostic measures to recalibrate over time. Ultimately, whether it is by telling the story of modernity, shining a light on outreach efforts, or just assisting those around the world who are countering extremists for their own reason, the approach must be sustainable and global in nature.

RADICALIZATION

Belarouci: The Genesis of Terrorism in Algeria

Dr. Latéfa Belarouci, a consultant, offered a historical overview of the development of fundamentalism and extremism in the Algerian context, noting that it was not a recent development, but instead grew out of the colonial experience. When the French colonized Algeria, they robbed the Arab populations of their identities, engaging in ethnic politics that equated the darker skinned, Arabic speaking Arabs as something different from the paler skinned Berbers and the French themselves. This destruction of collective identity and the subsequent marginalization of native politics created an environment fertile for Muslim extremism. After the accession to independence, the first constitution enshrined the special place of Islam and Arabic in the Algerian psyche and the 1994 amnesty gave terrorists reprieve, though not necessarily to their victims. Fundamentally, Dr. Belarouci’s presentation illustrated the importance of understanding the historical context when confronting terror and extremism.

Everington: From Afghanistan to Mexico

Alexis Everington of SCL made a presentation outlining recurrent themes relevant to radicalization that had arisen from projects SCL had conducted around the world. Key themes for consideration in strategic communications included: mobilizing fence sitters; identifying the correct target population; managing perceptions of common enemies; engaging in local infospheres effectively; controlling the event and the subsequent message; making use of credible messengers; and understanding the importance of perceived imbalance. Everington noted that these themes are shared but are important to different degrees. Strategic communication must acknowledge, understand, and use these themes and their levels of importance, in the fight against radicalization.

Frank Furedi: Radicalization and the Battle of Values

Dr. Furedi of the University of Kent, UK offered findings from his research and his experience as an observer of events in Europe. He concluded by attempting to refute six key myths including: that radicalization is predicated in an ideology; that radicalized individuals suffer from some psychological deficiency; that extremism is driven by poverty or discrimination; that the internet is a key mobilizer or cause of extremism; that oppressive acts abroad (i.e., Israel and Palestine) motivates extremism; and finally, the notion that extremism is directly related to Islam.

Sageman: The Turn to Political Violence

Dr. Sageman of the Foreign Policy Research Institute elaborated upon his view of the transition process to radicalization and then extremism. He detailed the stages of engagement with radicalism from disenchantment and the development of a sense of community with counter-cultural forces to further involvement and sometimes violent extremism. He noted that it was very rare for someone to be caught up in a counter-cultural milieu and then end up undertaking terrorist actions; however, he noted that much of this transition occurs at a very local, micro level – not through the internet or other media.

Casebeer: Stories, Identities and Conflict

Dr. (LtCol.)Casebeer’s presentation illustrated the power of narratives to motivate action and to provide an internally resonant message and rationale for action. He detailed the common structure of narratives and how they engage cognitive structures and impact reasoning, critical thinking, and morality. Fundamentally, he concluded that stories help mediate the divide between the initial stimulus to act and the ultimate action, if it ever reaches that point.

INFLUENCE/DETERRENCE

Trethewey: Identifying Terrorist Narrative and Counter-Narratives

Dr. Trethewey of Arizona State University offered a background on narratives throughout history and their uses in today’s context. In terms of the narratives themselves, and why they are critical to understand, humans have acted as narrators throughout history. Historically narratives have helped to answer three questions:

- How do people connect new information to existing knowledge?

- How do people justify the resulting actions we take?

- How do people make sense of everyday life?

Understanding narratives provides a shorthand introduction into cultural comprehension. The critical components of narrative systems are stories, story form, archetypes, and master narratives. Narratives do not provide a full history or full understanding, but perhaps they provide a shorthand understanding that can prevent or reduce the possibility of making strategic communication gaffes. Additionally, it may suggest something about how to amplify the voices that are doing some interesting narrative work. However, it was agreed upon that the United States needs to be careful in invoking narratives of ridicule, but explore how those narratives work in contested populations. Ultimately, the environment has a lot to do with how a radical message resonates with a population. The master narrative then is always grounded in cultural, social, historical, and religious assumptions and radical extremists take up and appropriate those narratives for their own ends. The role of the US government should be to better understand those narrative strategies and work toward more effective, equally-culturally grounded counter narratives.

Gupta: Mega Trends of Terror: Explaining the Path of Global Spread of Ideas

Dr. Gupta of San Diego State University presented the reasons why messages spread within societies. He began with the messengers, arguing that there are three main actors who are present and extraordinarily important to the spread of ideas. The first actor is the connector. The connectors are the social networkers with connections to many people and with the necessary social skills to connect people to other people or ideas. Then there is the maven or “the accumulator of knowledge.” This actor is a theoretician. The third critical actor is the salesman. Dr. Gupta noted that these individuals are present in many of the social and religious movements around the world. He then concluded that the environment or context must be ripe. Lastly, the message itself must stick to the receivers, or those who are necessary to support a movement. Dr. Gupta discussed three factors that cause a message to stick: simplicity, a compelling storyline, and the idea of impending doom should the audience not act. Ultimately, any individual within an audience who is captivated by the message will seek out the opportunity.

DERADICALIZATION AND COUNTER-RADICALIZATION

Horgan: Assessing the Effectiveness of Deradicalization Programs

Dr. Horgan of Penn State University emphasized the importance of distinguishing between deradicalization and disengagement in terms of violent extremists. In his research, Dr. Horgan has interviewed over 100 respondents—only one had said that he had no other choice but to join a radical group. He outlined key push factors for disengagement including disillusionment with the goals of the group and the group’s leadership. He also outlined the key objectives of deradicalization programs while highlighting the problems faced by deradicalization programs in Saudi Arabia.

Hamid: A Strategic Plan to Defeat Radical Islam

Dr. Hamid of the Potomac Institute emphasized the importance of confronting radicalization on its own territory using the metaphor of disease – not only must one treat the symptoms of the disease (terrorism), but one also has to treat the disease itself (the radical ideology). His key recommendations were related to preventing the formation of passive terrorists (on the fence) and interrupting the transition of the latter to active ones. These recommendations included making use of Fatwas denouncing terrorism; exploiting rumors to denigrate the heroic image of radicals; and instilling a sense of defeat in the mind of the radicals. Fundamentally, he emphasized the importance of understanding the underlying cultural paradigms that underpin these social movements. Additionally, based upon his personal experiences with and observations of radical Islamic groups over the last 25 years, he considered radical religious ideology to be the most crucial component of both the development of radicalization and any successful interventions against it.

Phares: Muslim Democrats

Dr. Phares, National Defense University, argued that there was irrefutable evidence that extremists were motivated by a similar and comprehensible ideology—that of global jihadism with two main threads: Salafism and Khomenism. Despite this jihadist underpinning, observers, and others in the West must be careful to distinguish between the three main threads of jihadism in usage: Jihad in theology, in history, and in modern times, which represents the current movement.

Davis: Day Two Wrap Up

Dr. Paul Davis of the RAND Corporation synthesized many of the ideas that had been discussed over the two-day workshop. He noted that throughout the workshop there had been consensus as well as debate. One of the points that participants have agreed upon is that it is folly to speak about “terrorists” as a monolith. It is critical to take a systems perspective where the individual components are differentiated, providing a number of leverage points for counterterrorism. Another striking debate that has taken place over the two-day workshop involved the relative emphasis that should be placed on the ideological end or religious aspects of the problem. Those who take the broadest view see the troubles the world is going through as another wave that will resolve itself in its own time. However, that sanguine view assumes that countervailing forces will eventually succeed. Conference participants are part of such countervailing forces. Dr. Davis also highlighted discussion over whether the United States should focus on its own values and stories or on focusing strategic messages about critical issues such as interpretations of Islam. Most conference attendees, he said, were skeptical about the latter. He also discussed lessons learned from the Cold War about the value of truthfulness and credibility in strategic communications, as distinct from baser forms of propaganda. Overall, Dr. Davis pointed out that many of the points that appeared to be in conflict at the conference are not necessarily so when it is realized that the United States can maintain one focus at the strategic level and allow those who are closer to the action to focus on the tactical, contextual, level.

Selected Chapters:

- Sudan Strategic Assessment: A Case Study of Social Science Modeling (R. Popp)

- Trajectories of Terrorism (T. Rieger)

Comments