Iran’s Post-ISIL Strategic Calculus

Question (LR2): What will be Iran’s strategic calculus regarding Iraq and the region post-ISIL? How will JCPOA impact the calculus? What opportunities exist for the US/Coalition to shape the environment favorable to our interests?

Author | Editor: Astorino-Coutois, A. (NSI, Inc).

Iran’s Approach in Iraq

A number of the Iran SMEs who contributed to this Quick Look characterized Iran’s approach in Iraq as “flexible” and “opportunistic,” rather than determined by a strict set of guidelines or strategies. Michael Eisenstadt and Michael Knights of the Washington Institute find Iran’s “strategic style” in Iraq to be “subtle and thrifty,” for example, in pursuit of what Alex Vatanka, an Iran scholar from the Middle East Institute, highlights as its ultimate security objective. That is, to prevent Iraq ever becoming a state that could threaten Iran as was done during the Iran-Iraq War—a time that remains in recent memory for many Iranians. This does not mean a failed state in Iraq, but does imply a militarily weak Iraq. In this regard, Iran could see US and Coalition efforts to build the Iraqi security forces into an inclusive and strong national force as a direct threat to its security.

Iran’s Post-ISIL Strategic Calculus

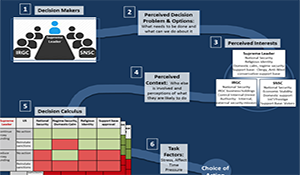

Cognitive decision researcher, Allison Astorino-Courtois (NSI), points out that an actor’s strategic calculus is context-dependent, and implies that a choice of behaviors is under consideration. There is therefore not a single strategic calculus that would explain the range of Iranian foreign policy choices and behaviors that US analysts and planners are likely to encounter. The good news is that while Iran’s tactics may change slightly, there is little to suggest that Iran’s key strategic interests will change with ISIL defeat: Iran saw what is perceived as Saudi-backed Sunni extremism as a significant threat before the emergence of ISIL, and surely will be prepared for the emergence of similar groups in the future.

The contributors to this Quick Look identified the following enduring strategic interests that should be expected to feature in almost any current Iranian calculus, as well as after the immediate threat of ISIL violence has weakened considerably. These are:

Safeguarding Iran’s national security by:

- Ensuring Iranian influence in the future Iraqi government, Syria, and the region as a whole to maintain the leverage to defeat threats to Iran posed by a pro-US and/or Sunni-inclusive Iraqi government

- Mitigating the security threat from Saudi Arabia and Gulf states, and decreasing Saudi influence throughout the region

- Eliminating the existential threat to Iran and the region’s Shi’a or Iran-friendly minorities from Sunni extremism, violent Wahhabism, and the re-emergence of ISIL-like groups

- Retaining and growing its influence in Lebanon and Gaza as leverage against Israel

- Combatting US regional influence in general

Defending Iran’s internal sovereignty by:

- Managing public dissatisfaction within Iran; quelling unrest

- Securing Iran’s borders and seacoast

Relieving economic stress and associated public discontent by:

- Defending Iranian economic assets and investments in Syria and gaining a foothold in the post-conflict economies (e.g., via construction contracts) in Syria and Iraq

- Working with other suppliers to increase global oil prices

- If and when Reformists are given leeway by the clergy and conservative forces in the Islamic Revolutionary Guards Corps (IRGC), opening economic relations with the EU

Defending the Islamic identity and leadership of the regime by:

- Clergy and Supreme Leader balancing the independent political influence of the IRGC against popular and reformist views in the government

Impact of JCPOA

Although as reported in SMA Reachback V6, other experts disagree on this point, Eisenstadt and Knights (The Washington Institute) believe that an unintended consequence of the JCPOA has been greater Iranian assertiveness in the region, and that “the more the US steps back in Iraq, the more Iran will step forward.” As a result, they argue, deterioration in US-Iran relations—perhaps as the result of a JCPOA-related crisis—could prompt an increase in Iranian challenges to US vessels in the region and arming of proxies. The implication is that the JCPOA may have increased the IRGC’s ability to argue for a more assertive regional policy, and that a new nuclear crisis could further strengthen their hand in this regard.

A political football? The success or perceived failure of the JCPOA may have important domestic political implications in the run-up to Iran’s May 2017 presidential election. Specifically, the perceived failure of the Agreement to produce widely anticipated improvements in the Iranian economy is a point on which President Rouhani and other reform-minded thinkers will be particularly vulnerable. In fact, Gallagher et al. (2016) reported this summer that while Rouhani was still the front runner, his lead over former president Mahmoud Ahmadinejad had dropped to a narrow margin largely on account of Rouhani’s perceived failure to improve the economy—a significant basis of the popular support for the JCPOA including that of supreme leader Ayatollah Ali Khamenei. This fall, apparently at the express request of Khamenei, Ahmadinejad announced that he would not run in May 2107 citing a meeting he had had with the supreme leader in which he was told that his candidacy would not serve the interests of the country. (Quds Force commander Major General Qasem Soleimani who also had been mentioned in the press as a potential candidate has similarly announced that he does not intend to run.) Speculation is that the Khamenei is determined to both avoid a repeat of the 2009 popular protests following Ahmadinejad’s divisive “stolen election”, and to put up attractive conservative candidates to challenge the relatively moderate Rouhani. However, there is also conjecture that Khamenei, who has been a vocal opponent of the JCPOA and a number of Rouhani’s other policies may not approve Rouhani’s run for re-election either. The official, vetted candidate list will be announced in April 2017. Finally, Eisenstadt and Knights (The Washington Institute) argue that to compensate the IRGC for acquiescing in the JCPOA, it has been given greater latitude to “(flex) its muscles abroad to demonstrate that it remains in control of Iran’s regional policies.”

Shaping Opportunities

The SMEs offer a number of suggestions for opportunities to:

Counter Iranian influence in Iraq

- Ensure long-term, multi-national commitment and funding to security in Iraq lasting beyond the war against ISIL (Michael Eisenstadt and Michael Knights, Washington Institute)

- Help the Iraqi Government resist Iranian pressure to institutionalize the PMUs as a military force independent of the Iraqi Security Forces (Eisenstadt and Knights, Washington Institute)

- Encourage Arab states to view the current Iraqi Government and press for influence on the basis of their common Arab identity, rather than continue to see the government as Shi’a first, and thus an inevitable ally of Iran (Alex Vantaka, Middle East Institute)

Increase stability in the region

- Provide Iran incentives for “positive behaviors” that reinforce its perception that it is succeeding in “re-creat[ing] the international order” (Bob Elder, GMU and Hunter Hustus, HQ USAF)

- Recognize that Iran views the Syrian War as “an existential matter for the Alawites in Syria and Shiites in neighboring states” and adjust US and partner activities to allay Iranian perceptions of sectarian threats (Bob Elder, GMU and Hunter Hustus, HQ USAF)

- Coordinate with Iran on pursuing the US shared interest in shoring up the stability and legitimacy of the Abadi government among Sunni Iraqis to reduce the appeal of violent jihadism among disaffected Sunni Iraqis (Bob Elder, GMU and Hunter Hustus, HQ USAF)

- Provide security/prestige guarantees to Iran in exchange for its encouraging sincere efforts at sectarian power-sharing by the Abadi government in Iraq (Allison Astorino-Courtois, NSI)

Contributing Authors

Eisenstadt, M. (Washington Institute for Near East Policy), Knights, M. (Washington Institute for Near East Policy), Vatanka, A. (Middle East Institute; Jamestown Foundation), Astorino-Courtois, A. (NSI), Elder, R. (George Mason University), Hustus, H. (HQ USAF), Nader, A. (RAND)

Comments