Coalition Activities and Terrorism

Question (S#1): What are the correlations between the US/coalition operational and tactical actions in theater effecting terrorist activity throughout the world (i.e., external events). For example, does the loss of ISIL controlled territory or kill/capture of an ISIL high value target lead to an increase/decrease in terrorist attacks in other areas of the world? Can location, intensity, duration or timing of attacks be predicted from a model?

Author | Editor: Ziemke, J. (John Carroll University).

The contributors weigh in on this question, doing their best to read the tea leaves. If Mosul should fall, what’s next? Where, when, and why?

Getting to the Where: Location

Jen Ziemke (John Carroll University) suspects that, in Iraq, as the primary focus otherwise shifts westward as the main front retreats toward Syria, it would be very prudent to continue to protect the rear from attacks on cities like Kirkuk. Regionally, continuing signs of instability in Saudi Arabia might place sites there at greater risk vis-a-viz some others. Due to their relative proximity to the battlefield, Beirut, Istanbul, or Amman continue to be at risk. Cafes, nightclubs, & bars in these locations are more imaginable choices than many other alternatives because such targets would serve to both maximize casualties and send a culturally-relevant message. Further afield, given the state of aggrieved populations in certain European suburbs, we suspect locations in Italy, France, and symbolic targets like the London Eye to continue to be at risk.

What about American targets? Victor Asal & Karl Rethemeyer (University of Albany SUNY) find that, despite the fact that “anti-Americanism is probably the most universal and widespread of attitudes,” the relative risk to American targets is low. However, the authors find that VEO’s are more likely to attack countries with American military bases, and that the risk of targeting is particularly acute when a significant number of American troops are stationed inside non-democratic countries, suggesting that their presence “may be generating a great deal of resentment. In addition to creating a motivation, the stationing of US troops abroad provides convenient military and civilian targets that can be killed without travelling to America.”

Timing is Everything: Battlefield Rhythms & Op-Tempo

Drawing from the literature on Complex Systems, Neil Johnson (University of Miami) argues that the timing of attacks follows reasonably well the “progress curve” (known from organizational development and learning literature). Similarly informed by a complex systems perspective, Ziemke asserts that converting conflict data into sonic landscapes for pattern analysis allows us to hear the battlefield rhythm and op-tempo of the conflict.

When micro-level event data (battles, massacres, ceasefires, etc) on the 41 year long Angolan war are played over time, we learn just how slowly these campaigns tend to begin. Like drops of water slowly coming out of a faucet, each individual event stands out because of the silence between events. From such analysis and observation, Ziemke asserts that losing groups do not go down quietly, nor without a fight, and what begins as individual events eventually turns into a firestorm of violence. But then, and even more rapidly, the fire dies, the losing side scatters, and the storm subsides. A few chirps amidst the silence mark the end, and the war dies in much the same way it starts, as an inverse refrain on how it began, little by little, punctuated by silences: an event here, an event there. Adagio crescendos to an absurdist cacophony, but just as quickly, it reverts to the same Adagio in the end. Thus, the start of the war helps to inform how it ends; it is actually the same melody, played again, but this time in reverse.

Severity

Neil Johnson (University of Miami) notes that the severity of any given attack “always seems to follow a so-called power-law distribution”, an occurrence repeatedly noted in the literature on conflicts and a feature of complex systems. This means that in every war, there are many events with relatively few casualties, but only very few events that are utterly catastrophic. Since extreme events and black swans are of heightened interest, when would we expect the risk of experiencing a catastrophe to be the highest?

Ziemke finds from her analysis of the Angolan war that when UNITA began to lose, they lashed out against civilians, and both the pace and severity of each event vastly increased. Losing is what accelerated the war into a new period, and a veritable cacophony of incredibly destructive events followed. It was as if an aggregation of losses on the battlefield ushered in a kind of phase transition in the war where extreme, rare events became more likely.

While in some ways ISIL strategy markedly differs from other violent groups, its tendency to lash out against civilians nevertheless may end up mirroring other quite different rebellions and insurgent organizations in history in terms of pattern, tempo, and timing. Consider, for example, the behavior of the RUF in Sierra Leone during their reign of terror under Operation No Living Thing, or UNITA’s appalling treatment of civilians during the latter half of the second Angolan war (1991-2002), or the surge in civilian deaths in Sri Lanka just before the LTTE was defeated in Sri Lanka in early 2009. Despite how different these organizations may be from one another, they share a common battlefield rhythm: when they began to lose the war, lose territory, and lose fighters, each group escalated their campaign to deliberately target civilians, and in increasingly grotesque ways, and even more than before.

Taken together, one might expect that if ISIL finds itself facing an imminent, existential threat to its survival, they might commit an unimaginable mass atrocity in whatever city they are entrenched, even if this behavior risks destroying a large number of their own fighters along with everyone else. As coalition forces continue to advance, one could imagine a David Koresh- style cult-like suicidal response, as many in their ranks might actually prefer this horrific outcome to defeat by another hand.

In the short term, as coalition forces render ever more devastating blows to ISIL, we fear that civilians in the area of operation may face even worse fortunes. However, when we begin to see ISIL commit massive atrocities on a previously unseen scale, the horrific events themselves likely are signals of their imminent defeat. The war (at least in the kinetic space, and in the near-term) will be nearing an end.

So what can be done to hasten ISIL’s demise?

Is targeted killing effective?

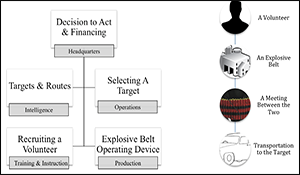

Rich Davis applies these questions to the Israeli-Palestinian conflict. He asks whether Israel’s targeted killing and apprehension program reduced the ability for Palestinian militants to project violence back into Israel. He finds that targeting Hamas’ militant network was effective and indeed led to a significant decline in both the number and lethality of suicide attacks by Palestinians inside Israel. The “further up the production line” the Israeli’s were able to penetrate, the better. As new militants who lacked experience replaced their deceased and/or imprisoned predecessors, less attacks occurred in general, and the attacks that did occur were less lethal. Additionally, as more and more of the network began to disintegrate, Hamas tended to allocate more resources “toward self-preservation, and less towards suicide attacks.”

Implications of Davis’ work applied to the Counter-ISIL campaign seem to suggest that missions targeting ISIL leadership might in the long-run lead to a decline in the ability of ISIS to project power and terrorize elsewhere, and that “the further up the production line” one was able to target, the better.

Somewhat in line with what Davis suggests, Johnston and Sarbahi also find that “drone strikes decrease the number and lethality of terrorist attacks,” at least in the short run. Taken together, the moral seems to be: “targeting works”. However, As Victor Asal and Karl Rethemeyer point out, research on the effectiveness of leadership decapitation, in particular, is mixed. Bryan Price suggests that leadership decapitation is only effective when applied to young groups. As groups mature, the effectiveness of leadership decapitation diminishes altogether. So if decapitation stands a chance of influencing outcomes with respect to the VEO under consideration here, the sooner, the better, and focus on the violence production line.

However, Victor Asal and Karl Rethemeyer suggest the reduction in violence might actually be due to the reconciliation efforts instead, and not the targeted killings. To conclude, one should ask: Historically, how effective has the use of violence been in terms of counteracting violence? Is using violence to counteract violence better than any of the alternatives?

Contributing Authors

Asal, V. (SUNY Albany), Davis, R. (Artis), Johnson, N. (University of Miami), Rethemeyer, R.K. (SUNY Albany), Ziemke, J. (John Carroll University)

Comments