Neurobiology of Aggression: Implications to Deterrence

*If you are having trouble downloading this publication, send us an email at info@nsiteam.com and we will send you a copy.

Topics in the Neurobiology of Aggression: Implications to Deterrence.

Author | Editor: DiEuliis, D. (HHS) & Cabayan, H. (Joint Staff).

This paper provides a series of selected topics on the neurobiological basis of aggression, in the interest of introducing this field of science to the community of experts in deterrence. Thus the topics covered are those of most relevance to inform a deterrence community of how neurobiological considerations may be incorporated as potentially useful tools in deterrence practice. The material is presented in 3 Parts: A summary of the basic neurobiology, a few chapters on behavioral impacts of that neurobiology, and finally a “systems summary” that integrates these issues for readers. Topics include the role of genes and environment, group vs. individual aggressive behaviors, the role of trust and altruism, reward/punishment, and premeditated vs. impulsive aggression, among others. The paper also discusses the continuum of scientific evidence base, from the basic neurobiology of reactive aggression, to pre- meditated aggression and what connections can be understood and conjoined to the psychological and behavioral evidence base.

Key insights provided by contributing authors to this white volume that are of particular relevance to the operational community include:

- It is not possible to understand the biology of behavior without understanding the context in which that biology occurs, as well as the society in which that individual dwells. This is true in our understanding of aggression; there is no highly accurate means of identifying individuals likely to commit an impulsive or planned violent act. The context in which aggression and violence occur can be modified much more easily than identifying individuals likely to commit aggressive act; by manipulating context, society may reduce aggression by individuals indirectly.

- Much aggression is motivated by conflict between in-groups and out-groups. An understanding of genetic and environmental factors can elucidate pathways toward aggression and begin to explain how various environmental factors such as media, propaganda, or informal mechanisms of narrative messaging, can be used to manipulate the neurobiological mechanisms that inform the psychological architecture of susceptible individuals. In that context, foreign policies which overtly impose governance or values alien to local cultures, may constitute provocations to violence.

- Within groups, punishment and reward cannot be understood outside the context of cooperation. Cooperation is stable when defectors can be identified, excluded and/or punished, and when prospective cooperators can be identified, engaged, and rewarded through cooperative exchange. Research indicates reward may function less effectively as a behavior-changing strategy, but may function more effectively as a behavior- sustaining strategy.

- Punishment in the context of group conflict cannot be understood absent the evolutionary logic of warfare between groups in an ancestral environment that was “offense dominant”. The “secure retaliatory force” that nuclear strategists argue is necessary for equilibrium in the nuclear age is nothing but a euphemism for “guaranteed vengeance,” in which states promise a punishment that is greater than the benefits of striking first.

- States where the rule of law is weak can beget societies characterized by “culture of honor” traditions, in which, in the absence of capable and legitimate third-party enforcement, reputation for disproportionate retaliation/punishment becomes the most effective safeguard against personal violence.

- Deterrence as a concept may be a long-learned part of our psychology. Because challenges, predators, or out-group threat have faced humans for millennia, analyzing the notion of deterrence from the perspective of evolutionary models may prove helpful. Rational actors have an interest in settling things with threats but without the use of violence. Vengeance is certain to be provoked by an attack, deterrence kicks in when the initiators cannot be absolutely sure that they’ll be successful.

- Neuroscientific studies of human behavior suggest aggression is a useful but costly strategy and people have a tendency to cooperate in many situations. This has been shown to be chemically regulated, and cooperative behaviors are just as “natural” as aggressive ones. The “Golden Rule” exists in every culture and reveals our essential social nature; this is naturally threatened in situations of threat or high stress.

- Neuroscience and technology offer a viable and potential value of in programs of national security, intelligence and defense. However this will necessitate an acknowledgement of the actual capabilities and limitations of the neuroS/T used – and importantly the ethico-legal issues generated by apt or inapt use, or blatant abuse.

- Context is critically important to our understanding of human behavior and biology is only part of what makes up our human selves and defines us as persons. An integrated approach, one that takes into account the influence of the empirical sciences as well as a social psychological framework, gives us the most holistic understanding of human behavior and produce the greatest improvement in our understanding of terrorism.

Topic Overview

In his introduction, Robert Sapolsky defines “aggression” in the fullest sense as harming, attempts to harming, and thoughts about harming. Two brain regions dominate this. The first is the amygdala, an ancient structure in the “limbic system” (the “emotional” part of the brain). The second is the frontal cortex (FC). It is more complex in humans than in other species, is the most recently evolved part of our brain, and is the last to fully mature (remarkably, in the mid- 20s). There are tremendous individual differences in FC function among people; many of differences arise from differing early life experiences. The limbic system/FC contrast can, in a thoroughly simplistic way, be thought of as a contrast between emotion and thought. A key issue is that genes have far less to do with aggression than is often assumed; genes are not about inevitability, rather, they are about proclivities. In conclusion, Professor Sapolsky states that amid this emphasis on biology, ultimately, it is not possible to understand the biology of behavior without understanding the circumstances of the individual in which that biology occurs, as well as the society in which that individual dwells.

In Part 1 (Aggression and the Brain), Allen Siegel discusses the two forms of aggressive behavior: predatory or premeditated aggression and affective or impulsive aggression. He points out that it is often difficult to detect any response patterns that could be used to predict the onset of predatory aggression – the behavior occurs with no perceived threat, is purposeful and planned, and appears to be devoid of conscious awareness of emotion.

Jordan Grafman and Pamela Blake provide further insights into the aggressive brain. They focus on laboratory work examining the key brain regions involved in impulsive aggressive behavior and control, the types of environmental exposures that could influence aggressive behavior, and the interaction of genetic predisposition, brain damage, and aggressive behavior. They report that specific brain lesions can affect impulsive aggressive behavior, and genetic predisposition can affect aggression as long as the key brain area mediating that effect is not damaged. There is no guarantee of accurately identifying people likely to commit an impulsive or planned violent act, rather, the context in which aggression and violence occur can be modified much more easily than identifying individuals likely to commit aggressive acts. By manipulating context, society can reduce aggression by individuals indirectly.

Peter Hatemi and Rose McDermott point out that much aggression is motivated by conflict between in-groups and out-groups. Aligned with other authors in this white paper, they note that studies of genetic and environmental characteristics can elucidate pathways of aggression. They can provide insights into how various environmental factors, such as the media, propaganda, and informal mechanisms of narrative messaging, can be used by ourselves, allies and adversaries to manipulate the neurobiological mechanisms that inform the psychological architecture of susceptible individuals. From this perspective, US interests may be better protected through the development of strategies to manipulate environmental triggers, and creation of interventions to address the human psychological architecture that responds to threat with aggression. Lastly, provocation is important in potentiating violence. Foreign policies which try to impose governments, institutions, or values alien to local cultures, are likely to be understood as constituting such provocations.

In Part II, some implications of aggressive behavior are presented. Anthony Lopez discusses the human psychology of reward and punishment in light of evolutionary pressures, and in the context of both in-group and out-group behavior. Within groups, punishment and reward cannot be understood outside the context of cooperation. Cooperation is stable when defectors can be identified, excluded and/or punished, and when prospective cooperators can be identified, engaged, and rewarded through cooperative exchange. Empirical data indicates that when punishment is available, cooperation is often stable and free-riding is deterred. Although research on the role of reward in promoting cooperation is relatively lacking, there are indications that reward may function less effectively as a behavior-changing strategy, but may function more effectively as a behavior-sustaining strategy. Punishment between individuals and groups takes the form of a withdrawal of benefits or the conferral of costs. Punishment in the context of group conflict cannot be understood absent the evolutionary logic of group warfare. Evolutionarily, warfare has most often taken the form of lethal raiding and it has occurred in an ancestral environment that was “offense dominant”. Lopez notes that the “secure retaliatory force” (touted by nuclear strategists as necessary for equilibrium in the nuclear age) is actually a euphemism for “guaranteed vengeance,” in which states promise a punishment that is greater than the benefits of striking first. States with weak rule of law beget societies characterized by “culture of honor” traditions, in which, in the absence of capable and legitimate third-party enforcement, reputation for disproportionate retaliation/punishment becomes the most effective safeguard against personal violence.

Rose McDermott and Peter Hatemi provide further insights into the role of emotion in decision making around violence. By exploring the foundations of human psychological and neurobiologically informed notions of threat and deterrence, we can begin to leverage our own biology in service of our very survival through recognition of those environmental cues and triggers which both instigate and extinguish our desires for aggression and cooperation. They discuss two key topics relevant to the theory of deterrence; namely the “Psychology of first strike, Coalitionary Humans, and Maximum Response” and “Leadership and Group Dynamics”. Following similar arguments advanced by Anthony Lopez, they argue that before nuclear weapons appeared, deterrence as a concept was naturally built into our psychology. Because humans have faced challenges, predation, and out-group threats for millennia, analyzing the notion of deterrence from the perspective of evolutionary models may prove useful; examining the genetic and biological mechanisms which precipitate our recognition and response to threat can inform our understanding of how to create more accurate signals and more effective responses. Rational actors may negotiate by using threats, without the use of violence. Where vengeance is certain to be provoked by an attack, deterrence kicks in when the initiators cannot be absolutely sure that they’ll be successful. The section on “Leadership and Group Dynamics” provides reasoning that evolutionary and neurobiological perspectives have served to enlighten aspects of leadership beyond that of traditional models. They propose that a more neurobiologically informed understanding of individual dispositions and personal psychology may reveal triggers that cue a particular individual to respond in a hostile as opposed to conciliatory manner in the face of threat.

In the last chapter in Part II, Paul Zak focuses on the role of hormones on the reduction of aggression. Episodes of aggression, especially repeated aggression by the same individual, are due to combinations of, and interactions between, genes, brains, history, and environments. Neuroscientific studies of human behavior suggest aggression is a useful but costly strategy and most people have a strong bias to cooperate in many situations. Zak demonstrates this is affected by the neuroactive hormone oxytocin (OT). OT appears to function as a chemical regulator that mediates prosocial behaviors by signaling that another person is safe or familiar, even if the other person is a stranger. One can make the case that cooperative behaviors are just as “natural” as aggressive ones, that cooperation with strangers is a typical human behavior, and that conflict among strangers may not be the norm. He reports that laboratory “trust games” capture, in an objective way, the notion of the Golden Rule: if you are nice to me, I’ll be nice to you. Of hundreds of people tested in a variety of cultures, roughly 95% of individuals reciprocate trust. The Golden Rule exists in every culture on the planet and reveals our essential social nature. It appears that OT is largely responsible for reciprocation by sending a safety signal motivating nice with nice. He goes on to point out the role of the environment and states that high stress can inhibit OT and put us into solitary or socially narrow survival mode. Environments that are unsafe, new, competitive, aggressive, or unpredictable induce greater release of certain hormones and thereby inhibit prosocial behaviors, especially such behaviors towards strangers.

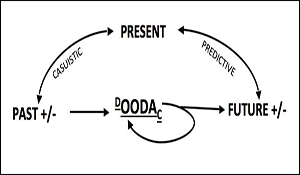

In Part III, James Giordano shifts focus towards weaving the basics of neuroscience and technology (“neuroS/T”) into social and cognitive aspects, creating a systems understanding. In a paper entitled “Toward a Systems Continuum: On the Use of Neuroscience and Neurotechnology to Assess and Affect Aggression, Cognition and Behavior” he argues that neuroscience has assumed a prominent role in shaping views of the human being, human condition, and human relationships. Neuroscientific discoveries continue to challenge and promote a re-examination of socially-defined ontologies, values, conventions, norms and mores, and the ethico-legal notions of individual and social good. As a potential analogous framework for “neurodeterrence” he introduces the concept of neuroecology – the study individuals’ neural systems, embedded in groups and environment(s) framed by time, place, culture and circumstance. Defining the neural bases of such biological-environmental interactions may yield important information about factors that dispose and foster various actions – including cooperation, conflict, aggression and violence. This emphasizes the viability and potential value of neuroS/T in programs of national security, intelligence and defense (NSID). He reiterates that any consideration of the possible use of neuroS/T for NSID would require acknowledgement of the actual capabilities and limitations of the neuroS/T used – and importantly, the ethico-legal issues generated by apt or inapt use, or blatant abuse. Otherwise there is a real risk that neuroscientific outcomes and information may be misperceived, and misused to wage arguments that are inappropriate or fallacious. He questions whether ethico- legal systems are in place and realistic and mature enough to guide, direct and govern such possible use and/or non-use. He goes on to state there is the need to develop stringent technical and ethico-legal guidelines and standards for such use of neuroS/T. He advocates a dedication to both ongoing neuroS/T research, and full content ethico-legal address, analyses and articulation of the ways that these approaches may be used, misused and/or abused in contexts of national security, intelligence and defense.

Neuroscience and technology offer a viable and potential value of in programs of national security, intelligence and defense. However this will necessitate an acknowledgement of the

actual capabilities and limitations of the neuroS/T used – and importantly the ethico-legal issues generated by apt or inapt use, or blatant abuse.

LtGen Robert Schmidle (USMC) in his closing editorial comment chapter entitled “An Integrated Approach to Understanding Human Behavior” proposes some final ideas in line with other contributors to this white volume. He stresses that context is critically important to our understanding of human behavior, and biology is only part of what makes up our human selves and defines us as persons living in a given society and culture. He discusses the terrorist as a behavioral example of purposeful aggression and violence. He advocates an integrated approach, one that takes into account the influence of the empirical sciences as well as a social psychological framework, gives us the most holistic understanding of human behavior. He stresses the need to develop a conceptual framework within which to conduct empirical investigations that includes the relevant cultural and historical context. In this instance, both kinds of knowledge, scientific, (i.e. empirical) and philosophic, (i.e. conceptual) are necessary for our understanding of human actions. He concludes by stating that while we may not ever definitively answer the question of responsibility for the development of a terrorist, for example, an integrated approach that takes into account both biology and psychology will produce the greatest improvement in our understanding of terrorism.

Contributing Authors

Robert Sapolsky, Stanford U; John Gunn, Stanford U.; Cynthia Fry Gunn, Stanford U., Allan Siegel, New Jersey Medical School; Jordan Grafman, Rehabilitation Institute of Chicago; Pamela Blake, MemorialHermann Northwest Hospital; Peter Hatemi, Penn State; Rose McDermott, Brown U; Anthony Lopez, Washington State U; Paul Zak, Claremont Graduate U; James Giordano, Georgetown U Medical Center; Roland Benedikter, Stanford U; LtGEN Robert Schmidle, USMC