Regaining Strategic Initiative in the Gray Zone

Outplayed: Regaining Strategic Initiative in the Gray Zone.

Speaker: Freier, N.

Date: June 2016.

INTO THE NEW GRAY ZONE

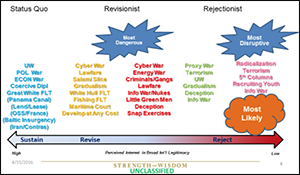

U.S. competitors pursuing meaningful revision or rejection of the current U.S.-led status quo are employing a host of hybrid methods to advance and secure interests that are in many cases contrary to those of the United States. These challengers employ unique combinations of influence, intimidation, coercion, and aggression to incremen- tally crowd out effective resistance, establish local or regional advantages, and manipu- late risk perceptions in their favor.

So far, the United States has not come up with a coherent countervailing approach. It is in this “gray zone”—the awkward and uncomfortable space between traditional conceptions of war and peace—where the United States and its defense enterprise face systemic challenges to U.S. position and authority. As a result, gray zone competition and conflict should be pacers for defense strategy.

DESCRIBING THE GRAY ZONE

For defense and military strategists, the gray zone is a broad carrier concept for a universe of often-dissimilar strategic challenges. Defense-relevant gray zone threats lie between “classic” war and peace, legitimate and illegitimate motives and methods, uni- versal and conditional norms, order and anarchy; and traditional, irregular, or uncon- ventional means. All gray zone challenges are distinct or unique, yet nonetheless share three common characteristics: hybridity, menace to defense/military convention, and risk-confusion.

First, all gray zone challenges are some hybrid combination of adverse methods and strategic effects. Second, they menace American defense and military convention because they simply do not conform neatly to a linear spectrum of conflict or equally linear mili- tary campaign models. Finally, they are profoundly risk-confused; as such, they disrupt strategic risk calculations by presenting a paralyzing choice between action and inaction. The hazards associated with either choice appear to be equally high and unpalatable.

For Department of Defense (DoD) strategists and planners, gray zone competition and conflict persistently complicate military decision-making, deployment models, and force calculations. They often fall outside the defense conceptions of war, yet they can rapidly and unexpectedly fall into them via miscalculation and unintended escalation. In the end, whether emerging via purpose or implication, gray zone challenges increasingly exact warlike consequences on the United States and its partners.

AN IMPERATIVE TO ADAPT

U.S. defense strategists and planners must dispense with outdated strategic assump- tions about the United States, its global position, and the rules that govern the exercise of contemporary power. In fact, the U.S. defense enterprise should rely on three new core assumptions. First, the United States and the U.S.-dominated status quo will encoun- ter persistent, unmitigated resistance. Second, that resistance will take the form of gray zone competition and conflict. Finally, the gray zone will confound U.S. defense strate- gists and institutions until it is normalized and more fully accounted for by the DoD.

These assumptions, combined with the gray zone’s vexing action-inaction risk di- lemma, indicate there is an urgent necessity for U.S. defense adaptation. Without it, the United States introduces itself to enormous strategic risk. The consequences associated with such failure to adapt range from inadvertent escalation to general war, ceding con- trol of U.S. interests, or gradual erosion of meaningful redlines in the face of determined competitors. These risks or losses could occur absent a declared or perceived state of war.

FINDINGS AND RECOMMENDATIONS

Examining the gray zone challenge through the lens of five archetypes—three state competitors (China, Russia, and Iran), one volatile environment (Middle East and North Africa), and the United States—this study arrived at six core findings and four recom- mendations. The findings and recommendations are statements of principle. The study team suggests that these principles will provide senior defense leadership with touch- stones for deeper examination. The findings and recommendations are broken into two major categories: policy and strategy, and operational plans and military capabilities. The former provide judgments affecting high-level DoD decision-making, while the lat- ter informs how the U.S. military might consider employing forces and assets.

POLICY AND STRATEGY

In the area of policy and strategy, this study found that there is no common percep- tion of the nature, character, or hazard associated with the gray zone or its individual threats and challenges. Consequently, there are gaps in strategic design, deliberate plans, and defense capabilities as they apply to operating and succeeding in gray zone environments. This study further found that there is significant asymmetry in risk per- ceptions between the United States, its partners, and their principal gray zone adver- saries and competitors. The results of this apparent asymmetry of risk-perception are predictable—loss of initiative, ceded control over interests or territory, and a position of general disadvantage in the face of aggressive gray zone competition. Finally, this study discovered that there is neither an animating grand strategy nor “campaign-like” char- ter guiding U.S. defense efforts against specific gray zone challenges. Because of this, U.S. gray zone responses are generally overly reactive, late, and ineffective.

In response to these findings, this study recommends that the DoD develop a com- mon, compelling, and adaptive strategic picture of the range of gray zone threats and their associated hazards. This new perspective should adequately assess the current gray zone landscape, the likeliest future trajectory of its constituent threats, and finally, the prospects for sharp deviations from current trends that might trigger a fundamen- tal defense reorientation. It further recommends that the DoD “lead up” and develop actionable, classified strategic approaches to discrete gray zone challenges and chal- lengers. Without a coherent approach to reasserting U.S. leadership, the United States risks losing control over the security of its core interests and increasing constraints on its global freedom of action.

OPERATIONAL PLANS AND MILITARY CAPABILITIES

In the area of operational plans and military capabilities, this study found that com- batant commanders’ (CCDR) presumptive future gray zone responsibilities do not align with their current authorities. Combatant commands (CCMDs) need greater flex- ibility to adapt to their theater strategic conditions, and must act to gain and maintain the initiative within their areas of responsibility. It further found that the current U.S./ North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) joint phasing model is inadequate to seize and maintain the initiative in the gray zone. Purposeful gray zone revisionist actors are successfully campaigning and achieving warlike objectives inside the steady state or deterrence phases of the U.S./NATO joint phasing model. Further, contextual forces of rejection are themselves accumulating warlike wins in the absence of a coherent non-linear U.S. approach. Finally, this study concluded that current U.S. concepts for campaign design, the employment of forces, and the use of force are not well-adapted to persistent gray zone competition and conflict.

To contend effectively with the implications of these findings, this study recommends the following initiatives. First, CCDRs should be empowered to “operate” against ac- tive gray zone competition and conflict with new capabilities and agile, adaptive models for campaigning. This implies that CCDRs should possess the requisite respon- sibility, authority, and tools essential to achieve favorable outcomes that are in their purview. In addition, this study found that the DoD and the Joint Force should develop and employ new and adaptable concepts, capabilities, and organizational solutions to confront U.S. gray zone challenges. It recommends a number of specific actions to improve U.S. military performance in the areas of ground and special operations forces (SOF), air and maritime capabilities, cyber capabilities, exercises, and power projection.

WAY AHEAD—ADAPTATION AND ACTIVISM

Normalizing and accounting for the DoD’s burgeoning gray zone challenge relies on the socialization of two important concepts—adaptation and activism. The defense en- terprise needs to adapt to how it sees its gray zone challenges; how it charters strategic action against them; and, finally, how it designs, prioritizes, and undertakes that strate- gic action. All of these require a robust and activist DoD response. To date, the United States favors approaches that are more conservative. This study suggests that continuing such approaches invites substantial and potentially irreversible strategic consequences.

Comments