New Face of Transnational Crime Organizations (TCOs)

The ‘New’ Face of Transnational Crime Organizations (TCOs): A Geopolitical Perspective and Implications for US National Security.

Author | Editor: Riley, B. (OSD/RRTO), Kiernan, K., St. Clair, C. (Kiernan Group) & Canna, S. (NSI, Inc).

Office of the Secretary of Defense

President Barack Obama: Significant transnational criminal organizations constitute an unusual and extraordinary threat to the national security, foreign policy, and economy of the United States, and I hereby declare a national emergency to deal with that threat…Criminal networks are not only expanding their operations, but they are also diversifying their activities, resulting in a convergence of transnational threats that has evolved to become more complex, volatile, and destabilizing.

Department of Defense Counternarcotics and Global Threats Strategy, 27 Apr 11: The 2011 White House Strategy to Combat Transnational Organized Crime defines TCOs as “self- perpetuating associations who operate transnationally for the purpose of obtaining power, influence, monetary and/or commercial gains, wholly or in part by illegal means, while protecting their activities through a pattern of corruption and/ or violence, or while protecting their illegal activities through a transnational organizational structure and the exploitation of transnational commerce or communication mechanisms.”

Transnational organized crime and transnational criminal organizations refer to a network or networks structured to conduct illicit activities across international boundaries in order to obtain financial or material benefit. Transnational organized crime harms citizen safety, subverts government institutions, and can destabilize nations.

James R. Clapper, Director of National Intelligence: Transnational organized crime is an abiding threat to U.S. economic and national security interests, and we are concerned about how it might evolve in the future. We are aware of the potential for criminal service providers to play an important role in proliferating nuclear- applicable materials and facilitating terrorism.

National Intelligence Council: Five key threats to U.S. National Security: (1) Transnational Organized Crime (TOC) Penetration of State Institutions; (2) TOC Threat to the U.S. and World Economy; (3) Growing Cybercrime Threat; (4) Threatening Crime-Terror Nexus; and (5) Expansion of Drug Trafficking (Mexican drug trafficking organizations continue to expand their reach into the United States.)

Department of Defense Counternarcotics and Global Threats Strategy: Transnational organized crime represents a significant, multilayered, and asymmetric threat to our national security…It is not viable for DoD to continue to examine this complex threat through the single lens of the drug trade.

General Martin Dempsey, Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, in an interview with NBC’s Ted Koppel on January 24th, 2013: …what we’ve had to do in response is we have become a network. To defeat a network, we’ve had to become a network…

General Stanley McChrystal, March/April 2011 edition of Foreign Policy: …to defeat a networked enemy we had to become a network ourselves. We had to figure out a way to retain our traditional capabilities of professionalism, technology, and, when needed, overwhelming force, while achieving levels of knowledge, speed, precision, and unity of effort that only a network could provide…

The continually evolving strategic environment coupled with the ascendant role of Transnational Criminal Organizations (TCOs) necessitates a comprehensive understanding of these organizations. TCOs represent a globally networked national security threat and pose a real and present risk to the safety and security of Americans and our partners across the globe. This challenge blurs the line among U.S. institutions and far surpasses the ability of any one agency or nation to confront it. Thus, countering TCOs necessitates a whole-of-government approach and, beyond that, vibrant relationships with partner nations based on trust. These are essential if the U.S. is to remain the partner of choice and effectively counter TCOs globally. Weak and unstable government institutions coupled with scarce legitimate economic opportunities, extreme socio-economic inequities, and permissive corrupt environments are key enablers that allow TCOs to operate with impunity. These same factors enable the emergence of violent extremist organizations (VEOs). The potential nexus between VEOs and TCOs remains an area of deep concern. In this context, deeper insight into the contemporary face of TCOs will facilitate the development of strategies to counter and defeat them. This white volume examines the “new” face of these transnational crime organizations and provides a geopolitical perspective and implications for U.S. national security. The nexus of culture and technology (including modern communication technologies) and their impact on the evolution of TCOs is discussed in addition to their implications for countering TCOs.

Key Insights

- Nature of Transnational Criminal Organization (TCO) threat

- TCOs represent a globally networked national security threat and pose a real and present risk to the safety and security of Americans and our partners across the globe.

- The struggle against TCOs is a long-term proposition, requiring continuous effort, creative solutions, and the assumption of some risk.

- This challenge blurs the line among U.S. institutions and far surpasses the ability of any one agency or nation to confront it.

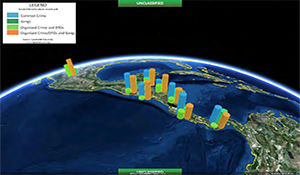

- The specific threats vary by region and sub-region.

- Many regions are plagued by a drug arm that is vibrant, expanding, and has both a solid supply and demand base.

- In many instances, criminal groups seem to be evolving towards a business model based on loose associations of individuals or small groups operating independently.

- Successful TCOs appear to adapt their operations to local conditions and geography.

- They utilize local resources and capabilities, outsource and enter alliances to further their interests, and rely on both local and global ethnic communities to network and operate.

- The connection of a TCO with a legal business operation lends an element of legitimacy to the group’s other activities.

- They operate legitimate businesses as front companies to help launder money associated with illegitimate activities.

- Members and senior leaders may participate in public or private political, charitable, or social events attended by highly placed political, business, and community leaders.

- They exploit legitimate commerce and, in some cases, create parallel markets.

- Key enablers that allow TCOs to operate with impunity include

- weak and unstable government institutions that have limited reach and presence into the furthest corners of society;

- scarce legitimate economic opportunities that entice citizens to cooperate with TCOs for security and economic well-being;

- extreme socio-economic inequities that open some geopolitical regions to a much greater risk of criminal or ideological manipulation and growth than others;

- permissive environments, loose financial controls, widespread corruption, and fraudulent document facilitation networks;

- extreme interconnectedness and gaps in socio-economic and political equity creating and overall environment favorable to the formation and continued growth of TCOs; and

- globalization via Information and Communications Technologies (ICT) transforming an increasingly hyper-connected markets and economies blur boundaries and even authority across socio-political processes and State control.

- Recent analytical work based on empirical data indicates, however, that a large percentage of the countries where convergence between TCOs and VEOs is prominent are among the richest in the world. The reason for this might be that TCOs and VEOs converge in their mutual interest to create and operate in ungoverned spaces despite having different ends.

- Bottom line: The ability of TCOs to use violence or threat of violence to achieve their aims renders no one immune irrespective of governance because all system are vulnerable from a micro or individual level

- Nexus of TCOs and Terrorist Organizations

- In many war zones and in ungoverned spaces across the globe, criminal and terrorist groups have formed once-improbable relationships, finding new ways to collaborate with each other.

- Environments most conducive to the formation and support of TCOs possess the same characteristics as those favorable to VEOs.

- Organized crime not only sustains insurgencies from a financial standpoint, it also supports their asymmetric warfare campaigns.

- This VEO/TCO convergence can be tremendously corrosive and also self- reinforcing.

- On the other side of the coin, an insurgency can lose both its standing with the population and its internal sense of political identity because of criminalization. This can be exploited in a counterinsurgency campaign.

- However, not in all instances is there such a proven nexus and in many instances, the degree of overlap is difficult to determine.

- Recent analytical work based on empirical data indicates that interconnectivity is greater than one might have predicted.

- Hybrid organizations (those that include both political extremist and criminal elements) are more of a threat across threat domains (radiological/nuclear [RN] smuggling, RN smuggling with extremist organization involvement, nexus formation, and instability threat) than are the more purely criminal organizations.

- Top level considerations to countering and defeating TCOs

- Countering TCOs is defined as the means to detect, counter, contain, disrupt, deter, or dismantle the transnational criminal activities of state and non-state adversaries threatening U.S. and partner nation national security. This will require the following:

- dismantling their networks across the globe and driving down their impacts to levels that can be handled by local law enforcement organizations;

- fostering a transnational, cross-organizational response and development of strategic security partnerships;

- coordinating intelligence and law enforcement actions between organizations and sharing data from a variety of organizations across the globe to identify criminal networks and activities;

- developing a comprehensive Counter Threat Network approach, whole-of- government, whole-of-societies collaboration, and possibly even new structures; and

- deploying teams of globally focused financial and fraud investigators to follow the illicit money supporting TCO and insurgent networks.

- Recent analytical work based on empirical data suggests that it is difficult to disrupt the activities of the global network by targeting a few kingpins and that the most effective means of countering such a global illicit network should involve a mixture of tools used to counter criminal activity in conjunction with those used to counter terrorism.

- Whole-of-governmentapproach

- Combating Transnational Criminal Organizations (CTCO) activities are primarily interagency in nature with many authorities, capabilities, and capacities beyond the scope of DoD requiring a whole-of-government approach.

- Taking the whole-of-government approach in support of law enforcement agencies has helped build a cooperative partnership of networks to counter transnational organized crime.

- The USG needs to develop a doctrine for stabilizing territories plagued by the crime-terror nexus and putting a focus on de-conflicting the work of disparate U.S. agencies, and crafting holistic strategy.

- The USG needs to create trans-agency teams that would integrate military forces, diplomats, reconstruction and development specialists, and legal experts tasked with reestablishing the authority, legitimacy, and effectiveness of the state in a target zone.

- However, barriers remain to achieving a universal realization of TCOs as a true threat to homeland security.

- Sometimes interagency legal wrangling, sensitivities, parochialism, diminishing resources, and old-fashioned bureaucracy stymie U.S. responses.

- Specific DoD role

- DoD brings to the government unique capabilities including

- comprehensive, disciplined, and finely developed capacity to develop complex strategic plans;

- global reach as well as unique and substantial resources;

- collaborative partner capacity building;

- certain counternarcotics authorities to assist law enforcement agencies;

- capability to detect and monitor illicit trafficking and disrupt the illegal flow of precursor chemicals; and

- intelligence analysis and information sharing.

- There is, however, a lack specific knowledge of those capabilities and the processes used to obtain them within the interagency.

- Improvements in key areas are identified:

- training programs to educate DoD analysts and planners on how organized criminal groups operate and how law enforcement and other governmental groups counter organized crime;

- assigning more representatives from U.S. government agencies and organizations involved in combating organized crime to DoD organizations; and

- reviewing and streamlining authorities pertaining to DoD’s support to law enforcement as well as regulations regarding the sharing of intelligence information.

- Role of partner nations

- Building the capacity of our partners to exercise their territorial sovereignty is crucial.

- Vibrant relationships based on trust are essential if the U.S. is to remain the partner of choice and effectively counter TCOs globally.

- Role of strategic communication in CTCO

- Strategic communication should rise to the level of main focus in many instances rather than remain a supporting effort with unachieved potential.

- The nexus of culture and technology in the evolution of TCOs and implications for countering CTO strategies: an evolutionary biological perspective

- The socio-technical nature of globalization is no longer treatable as separate elements.

- Current and future TCOs will be geographically and culturally dispersed.

- They will exhibit different socio-political tendencies and values.

- They will evolve different socio-technical infrastructures to support and protect their activities.

- They will mutate in response to environmental pressures ranging from market opportunities to government stability and even emergence of other criminal or VEO groups.

- Multiple and repeated interactions between system entities and individuals generate macro-level characteristics and dynamic patterns not found at the micro-level.

- They will operate as fully developed platforms for innovation that compete violently with each other and provide deviant entrepreneurs key advantages.

- The result is a strategic environment where disruptive ideas rapidly become products or processes that are tested in the real world very fast; success is easily imitated and iteratively improved.

- Modern communication technologies together with the explosion of electronically available information have

- hyper-connected markets and societies across the globe;

- enabled expansion of TCOs into emerging markets; and

- allowed TCOs to rapidly recruit expertise and employ various skills on a temporary or transient basis without the need to formally augment their enterprise. (Similarly, VEOs may recruit and sway sympathetic individuals without relying on old methods of radicalization or complete indoctrination to the cause.)

- Technological breakthroughs and their impact

- Advances in additive manufacturing, online anonymity, anonymizable currencies, and communication technologies amongst others have the potential to change the contours of the landscape entirely.

- They increase the potential for violent upheaval and instability because they empower greater numbers of individuals

- Modern communication technologies make it much more difficult for law enforcement to monitor and/or trace communications and financial flows among nodes in the networks.

- Implications for countering TCOs

- Deviant innovators have one essential business requirement: to be one step ahead of the governmental deployment of interdiction technologies to remain a profitable operation while being ready to hack new inventions as soon as they are deployed.

- This necessitates that governments respond accordingly

- The USG should constantly play the role of TCOs, penetrating governmental technologies.

- Policies should be designed in a way that whenever the environment changes, the shape of the governmental response can change with it.

- Think at the scale of big technology trends, devaluing the importance of any individual adaptation in any threat assessment.

- Cyberspace offers a solution in terms of collaboration environment providing CTCO groups a data ecosystem that is fluid enough to let organizations innovate from the bottom up in response to local conditions. On the other hand, balancing competing needs for security and access provide scaffolding for an entire range of cyber-enhanced capabilities. This three-element structure allows coordination and collaboration in local spaces, as well as global data sharing.

- A better fundamental characterization of the cyber-socio-technical nexus can help form cogent U.S. defense-related policies and guidance for operational context.

Contributing Authors

Mr. Gary Ackerman (START); Maj David Blair (USAF/Georgetown University); Ms. Lauren Burns (IDA); Col Glen Butler (USNORTHCOM); Dr. Hriar Cabayan (OSD); Dr. Regan Damron (USEUCOM); Mr. Joseph D. Keefe (IDA); Col Tracy King (USMC); Mr. David Hallstrom (JIATF West); Dr. Scott Helfstein (CTC); Mr. Dave Hulsey (USSOCOM); Mr. Chris Isham (JIATF West); Ms. Mila Johns (START); Mr. James H. Kurtz (IDA); Dr. Daniel J. Mabrey (University of New Haven); Dr. Vesna Markovic (University of New Haven); MG Michael Nagata (Army, J-37); Dr. Rodrigo Nieto-Gomez (NPS); Ms. Renee Novakoff (USSOUTHCOM); Ms. McKenzie O’Brien (START); Dr. Amy Pate (START); Ms. Gretchen Peters (George Mason University/Booz Allen Hamilton); Mr. Christopher S. Ploszaj (IDA); BG Mark Scraba (USEUCOM); Mr. William B. Simpkins (IDA); Dr. Valerie B. Sitterle (GTRI); Mr. Todd Trumpold, (USEUCOM); Mr. Richard H. Ward (University of New Haven); Mr. Tom Wood (JIATF West); Dr. Mary Zalesny, (CSA SSG, PNNL)

Comments