Alleviating US-Iran Tensions

Question (R4.6): What are the competing national interests of the United States and Iran in the Middle East and what are the options for alleviating United States / Iranian tensions to mutual satisfaction and improved regional stability?

Author | Editor: Astorino-Courtois, A. (NSI, Inc).

Executive Summary

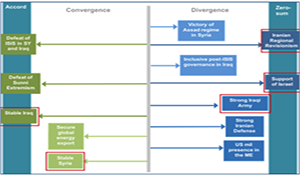

The US and Iran have the same types of interests — national security, international influence, economic, and domestic political—at stake in the conflicts surrounding Iraq and Syria. However, the different ways that each country currently defines these interests places them on a continuum that ranges from full accord over select regional issues to complete, zero-sum discord. This is an important point and one very pertinent to the question of alleviating US-Iran tensions: Iran and the US do not disagree on everything and national security is not always the primary issue at stake. The most promising avenue to alleviate tensions therefore may be to focus on issues on which US and Iranian interests tend to converge. However, there may be more leverage over what seem to be fully divergent interests than at first appears.

Convergent Interests: Stability in Syria, Stability in Iraq

Regardless of current US policy, the defeat of ISIS, followed by relative stability in Iraq and Syria are in the interests of both Iran and the US. For Iran, there are potentially huge post-conflict reconstruction contracts in the offing in Syria, provided the Syrian regime is friendly or weak enough for Iran to control a large part of that business. The earnings could be a boon for Rouhani and the moderate leadership in Iran who had promised yet-to-be-see Iranian gains following the Iran Nuclear Deal (JCPOA). US security interests in the region also are not served by instability in Syria, even if this means abiding by a weakened Assad regime for the immediate term.

Diverging Interests: Strong Iraqi Army

The strengthening of the Iraqi Army is a contentious subject between the US and Iran. The US would like to have influence in Iraqi military institutions, as would Iran. The ideal outcome for the US appears to be a professionalized Iraqi military strong and capable enough to secure its borders, maintain internal stability, and clamp down on radical extremist organizations in Iraq and elsewhere. While it is in Iran’s interests to see a security force in Iraq strong enough to maintain internal order and put down any resurgence of Sunni extremism, an Iraqi force strong enough to pose a threat outside Iraq’s borders is something no Iranian leader likely could or would support. The horrors and trauma of the Iran-Iraq War are still in the vivid memories of a good portion of the Iranian population.

Complete Divergence: Regional Security and Israel

Probably the most rigid points of conflict in US and Iranian interests involve how each defines regional security and, as a result, which actions and actors it perceived as threatening. Iran scholar, Dr. Payam Mohseni of Harvard University, identifies two security issues that serve as “the cornerstone” of US-Iran antagonism: “revisionism for the security architecture of the Middle East” including eliminating US military influence in the Middle East following ISIS defeat, and support of or opposition to Israel.

Iranian Revision to Regional Order.

Iran has long had a goal of changing the power dynamics in the Middle East region. This serves multiple Iranian interests simultaneously and shapes the policies it pursues. First, from the Iranian perspective, expanding its reach via Shi’a groups in Iraq, the Gulf, and Lebanon is an important means of defending Iranian security in a region in which it is a minority. Considering what Iran perceives as its main security threats (e.g., Saudi Arabia and Israel—both backed by US force), together with a desire for regional recognition and prestige, explains Iran’s attachment to a nuclear program. Revisions to the current system that enable Iran to exert additional regional influence and establish additional economic ties also serve the domestic objectives of the more moderate political and commercial elite.

Israel.

Ironically, relations with Israel serve the US and Iran in similar ways. Support for Israel is a consistent element of US foreign policy and is very much tied to US electoral politics. Since the Iranian Revolution, the Government has used its strong opposition to the security threat posed by Israel and the West to garner domestic approval and underscore its break from the Iran of the past (i.e., its revolutionary bona fides) to enhance its (self-proclaimed) legitimacy as the regional protector of the Muslim people.

Both Iranian and US security concerns are indelibly intertwined with the desire of each to increase regional influence and prestige, and to some degree, domestic support. An argument can be made that this coupling of interests is what generates the zero-sum quality of the US and Iranian positions and makes mutual animosities so easy to ignite. A situation perceived as zero-sum, “I win-you lose” by definition is one in which mutual gain is not possible; antagonism is assumed. As a result, all action by the opponent is perceived as competitive and, in the strategic sense, the only options available to each side are opposition or capitulation.

At present, both US and Iranian policy-makers imagine the regional expansion, influence, and attempts to change the regional order by and of the other as important threats to their own security and prestige. In this context, a perceived security gain for the US or its allies, for example by increasing the presence of US forces in the region or inking a $110 billion weapons deal with Saudi Arabia, inevitably is a loss for Iran. Similarly, an Iranian gain, for example increased influence within the Shi’a-led government in Iraq; professionalization and institutionalization of “mini Hezbollahs,” or IRGC clones in the Iraqi armed forces, is seen in the US primarily as Iranian aggression.

Can tensions be reduced? No. Not without reconceiving the US approach

Fortunately, the zero-sum nature of US and Iranian perspectives on these critical issues is not a mathematical absolute (as suggested by the term). Rather, US decision makers interested in alleviating tensions with Iran must recognize that the intractability in how the US and Iran have conceived of regional security is a psychological construct, in large part based in mutual uncertainty about what the other will choose to do. While it may require considerable cognitive and perhaps emotional effort to accomplish, reconceptualizing how the US approaches Middle East regional security and Iran’s role in it is very possible.

Mohseni emphasizes not just the possibility but the urgency of making these changes in US thinking. He argues that changed and changing conditions in the Middle East now demand rethinking of US interests in the region and the threats that it perceives from Iran: in “today’s increasingly fractious and unstable Middle East, it is all the more important to understand where and how the United States and Iran can see eye-to-eye.” He strengthens this argument with the discerning observation that even if the US were to succeed in containing Iran and eliminating the security threat that Iran poses to US allies in the region, some of the most pressing threats in the region, like the spread of violent jihadism and insurgency and political instability in traditional US allies, will remain. Critical threats to US interests and allies will not be mitigated by weakening Iran. This new context requires new thinking.

How? Small steps

If not seeing completely eye-to-eye, alleviating tensions essentially means that diverging Iranian and US interests are moved closer together; toward convergence. Each of the contributors suggests that this can only happen via direct engagement with Iran, which is essential not only for alleviating US-Iran tensions, but indeed for defending the US’s own security interests in the region. First, Dr. Daniel Serwer (Johns Hopkins SAIS) argues that US-Iran tensions cannot be overcome in a bilateral setting, but instead that a regional security architecture that could help reduce tensions among other regional actors and on other issues (e.g., Sunni-Shi’a competition) is needed. In a similar vein, SFC Mark Luce (USASOC) suggests using diplomacy to reduce Iran’s isolation by, for example, opening dialogues with Iran and Russia on Afghanistan and counter-VEO activities, encouraging others to expand diplomatic and economic relations with Iran, and providing US security guarantees to Saudi Arabia and the Gulf states in the event of Iranian aggression. While negotiating these arrangements certainly would require time and significant US domestic and regional resolve, other experts suggest more tactical and short- to mid-term steps for initiating US-Iran cooperation. Specifically, Dr. Laura Jean Palmer-Moloney (Visual Teaching Technologies) and Dr. Alex Dehgan (Conservation X Labs) cite the value that Iran has historically put on science, and suggest scientific exchange particularly on water, food, and energy issues. They note that Iranian scientists already “co-author more scientific papers with US scientists than with scientists of any other country,” and that US-trained STEM scientists serve in key positions in the Iranian government.

Contributors

Alex Dehgan (Conservation X Labs); Mark Luce (USASOC); Payam Mohseni (Harvard University); Laura Jean Palmer-Moloney (Visual Teaching Technologies, LLC); Daniel Serwer (Johns Hopkins School of Advanced International Studies, SAIS)

Comments