Successful Campaign Against ISIS

Question (R4.4): What does a successfully concluded campaign against ISIS look like? Considering costs, reputation, and balance of influence, how should the U.S./Coalition define success? Is the defeat of ISIS a success if it causes the balance of power in the region to shift towards Iran, Assad, or Russia?

Author | Editor: Hayes Ellis, D. (University of Maryland).

Executive Summary

Scoping “Success”

The responses provided to this question have either directly or implicitly pointed to a divide between what should be considered a “successfully concluded campaign against ISIS” in the operational theater in Syria and Iraq, versus at the global, strategic level. Standards for defining success on both levels tended to coalesce around similar benchmarks across all the responses.

Success at the Theater Operational Level

There is broad consensus among the respondents that a successfully concluded campaign against ISIS at the operational level, does not have to be defined by the total destruction of the group. Rather, a significant degradation of capabilities (particularly the ability to hold territory and the capacity to carry out extensive or highly lethal attacks), coupled with a reduction of the group’s threat to overall U.S. policy interests in the region, may be sufficient. Liebl offers that the total destruction of the group should be an aspirational goal, but acknowledges that this is unlikely in the near term and so success should be defined by different metrics. Braun suggests that the ISIS must be perceived as having been defeated to prevent the remnants from transmogrifying into some other virulent regional or global movement. Itani explicitly states that ISIS is an important threat at an operational level in Syria and Iraq; the danger is not existential to the US. Some respondents (Maye and Serwer for example) also noted the importance of creating stable circumstances for civilian populations, in the aftermath of a kinetic victory over ISIS and their subsequent loss of territory across the region. The challenges of this, particularly in avoiding redistribution of land and other assets away from the original owners, as well as avoiding the Iraqi perception that ISIS is being replaced by a hostile Shia regime, are well noted.

One point of divergence on specific metrics of degraded capabilities is based on the notion of organizational decapitation. Some responses (Lustick, Ligon, et al) make a case that success must include the elimination of ISIS leadership. Ligon and her colleagues make a more tactical argument, analyzing the data on the capacity of ISIS to carry out sophisticated and deadly attacks during times when the leadership is strong and organized, versus times when it is weak and in transition. Their analysis makes a compelling case that decapitation would severely hamper the operational effectiveness of whatever remained of ISIS forces. Other respondents raise doubts over the efficacy of a decapitation strategy noting that the targeted killing of many key militant leaders over the last sixteen years has not produced a long-term degradation of the threat (see Smith for example).

Success at the Strategic Level

“Successful elimination/destruction of Da’ish won’t occur in any conventional sense on the battlefield in Iraq, Syria or elsewhere,” writes Burki. In one sense or another, most of the respondents concur that strategic success against ISIS cannot be measured through the same lens as operational success in Syria and Iraq. Some authors (Ligon, Liebl, Lustick, and Burki for example) point to the ongoing capabilities of ISIS fragments and their tendency to recruit and embed themselves in Iraqi populations, in order to conduct ongoing social media strategies and to generally remain a presence on the global scene. They point out that the vast corpus of media and messaging already produced by ISIS can continue to radicalize individuals around the world and that their message may be just as focused on “martyrdom” as it was when they were highly successful on the battlefield.

An additional argument (Marten, Burki, and Anonymous) raises the prospect that at a strategic level, success against ISIS may not be a relevant concept as long as the overall concept of Salafi Jihad is not defeated. Strategic success in this view is less defined by the existence of the group itself and more by mitigating the circumstance that allow it to proliferate and thrive. The theme of the disenfranchisement of Sunni populations and the broader and more pressing struggle between Sunni and Shia forces in the MENA region, directly links to the rise of ISIS and other groups. These authors also tend to question the ability of the US to play a decisive role in achieving strategic success in this arena—casting much of the regional responsibility back to the local populations in conflict.

In looking at the big picture, Venturelli argues that success can be advanced through two strategies: 1) creating an integrated approach at the theater, strategic, and balance of power levels (Iran, Russia, Syria) and 2) focusing on the ‘exploitation’ of opportunities created by ISIS across these success components. This analysis rests on the belief that the situation in the Middle East presents opportunities to reshape MENA security and order and to mitigate challenges more effectively.

Is a Defeat of ISIS a “Success” if the Balance of Power Shifts to Favor Russia, Iran, or Assad?

Keeping with an orthodox view of US policy goals, the majority of respondents who addressed this sub- question indicate that a shift in the balance of power to favor Russia, Iran, or Assad, would undermine or negate the value of ‘defeating’ ISIS. Conversely a few contributors disagreed with that assessment, parsing the issues into very separate responses by actor, or disputing the validity of the question’s premise altogether.

The most in depth analysis (Itani) casts a post-ISIS state of play that sees an ascendant Iran as anathema to US interests; however, Russia is viewed as an actor that can more easily be accommodated in an acceptable regional framework. “Belei’s analysis views a post-ISIS future that favors Assad as a pessimistic scenario, but one which is very “likely.” Burki’s analysis rejects the entire premise of the sub-question and re-frames it from an operational space to a strategic one, stating that the relevance of the defeat of ISIS is not about a power vacuum in Syria, but rather its impact on the global trends in Salafi Jihadism—pulling us back to the point made above.

Contributing Authors

Anonymous 1, Bogdan Belei (Carnegie Endowment), Shireen Khan Burki (Independent), Aurel Braun (University of Toronto & Harvard University), Faysal Itani (Atlantic Council), Vern Liebl (Marine Corps University), Gina Ligon, Margaret Hall, Michael Logan, Clara Braun, and Samuel Church (University of Nebraska, Omaha), Kimberly Marten (Barnard College), Diane Maye (Embry-Riddle Aeronautical University), Ian Lustick (University of Pennsylvania), Pix Team (Tesla Government Services), Daniel Serwer (Johns Hopkins University), Janet Breslin Smith (Crosswinds Consulting), Martin Styszynski (Adam Mickiewicz University), Shalini Venturelli (American University)

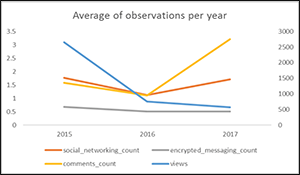

Comments