Denying the Seeds of Future Conflict

Question (R6.1): What conditions (demographic, political, etc.) should exist on the ground in the Middle Euphrates River Valley and the tri border (Syria/Jordan/Iraq) region to deny the seeds of future conflict from being planted – particularly taking into account the assumed intention of Iranian proxy forces to establish a Shia “land bridge?” Which of these conditions can and should be insisted on as part of a Geneva peace process to end the current conflict in Syria?

Author | Editor: Aviles, W. (NSI, Inc).

Executive Summary

Ambassador James Dobbins and a team from the RAND Corporation contend, “the Syria civil war is approaching, if not a conclusion, at least a hiatus that might be converted into a conclusion.”1 Major regional players—United States, Russia, and NATO—have a converging interest in ending the conflict and facilitating a stable peace, Dr. Amir Bagherpour of giStrat argues. However, despite an emerging shared preference between Russia and the United States on ending the conflict in Syria, rivalry dynamics between Turkey, Saudi Arabia, Iran, Qatar, and the UAE will likely have a dampening effect on peace prospects as the proxy warfare intensifies following the military defeat of Da’esh. Mr. Hassan Hassan of Tahrir Institute for Middle East Policy warns that the worsening of the various conflicts in the region is still a serious possibility.

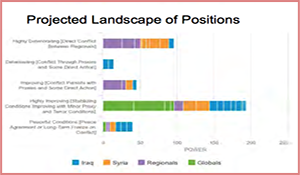

As the fight against Da’esh winds down in Iraq and Syria, brewing tensions and conflicts between regional actors and proxy groups is gaining new momentum. We asked thirteen regional experts to identify the top conditions necessary to bring an end to conflict in the region as well as effect a stable peace. Figure 1 captures several thematic categories of conditions posited by the authors in rank order as well as the estimated likelihood of occurrence.

Reduction in Proxy Forces

GiStrat’s computational modeling found that “the most significant factor for creating stabilizing conditions in the Euphrates River Valley is a reduction in proxy support by opposing larger powers,” a condition that seven other contributors agree is an essential criterion. Saudi Arabia, Qatar, Turkey, Russia, and the United States all support or fund proxy forces, but several experts emphasize Iranian proxy operations as the primary aggravating obstacle to peace in the region (Cafarella, Ganor, Jeffrey). Mr. Mubin Shaikh,3 an extremism expert, and Dr. Abdulaziz Sager of the Gulf Research Center both write that undermining pro-Iranian militias are the key to disrupting the Shia crescent “land bridge,” which Shaikh argues already effectively exists across Iraq and Syria.

Removal of Violent Extremist Organizations (VEOs)

The removal of Da’esh and Al-Qaeda in Iraq and Syria is mentioned by three authors4 who distinguish these groups from other proxy forces in the region. Dr. Martin Styszynski of Adam Mickiewicz University in Poland argues that the “defeat of ISIS’ structures in Syria and failures or withdrawal of Islamist insurgents” has allowed for high-level consolidation of strategic territories between Russia, Iran, and Turkey. Ms. Jennifer Cafarella of the Institute for the Study of War views the removal of Sunni VEOs in the tri border region as fueling the Assad regime’s advantage over the Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF) and weakening the likelihood of Assad to negotiate. Both contributors suggest that the demise of proxy groups and VEOs expose the underlying obstacles to a peace accord and the dormant mechanics of any future political settlements.

The Role of the Assad Regime in Peace

Contributors present a spectrum of possibilities on the fate of Assad’s continued leadership in the event of a lasting peace in Syria. One school of thought holds that regime change is absolutely necessary to a 2020 Geneva agreement (Ganor, Itani) while another holds a more moderate view that Assad will only need to exit at some point in the future (O’Shaughnessy, Yacoubian). The middle of the spectrum recognizes that the survival of the Assad regime is likely but his power will be constrained (Jeffrey) and concessions will be made to “opposition groups in Northern Syria, Southern Syria, and the Kurdish territory” (Bagherpour). The other extreme assumes that Assad has all but guaranteed a role in post- conflict Syria, that “the surrender of oppositions groups is certain,” and that Assad will emerge as victor (O’Shaughnessy).

Power Sharing and Territorial Concessions

The fluid and disparate landscape in the triorder region understandingly necessitates a peace process that will be predicated on numerous, multivariate resolutions where stakeholders concede a significant amount of geopolitical capital. Almost all of these concessions described by contributors involve dyadic relationships and are comprised of territorial cessation, decentralizing political governance, or military mobilization/de-escalation. Mr. Faysal Itani of the Atlantic Council lists a territorial partition as absolutely essential to peace while Ms. Cafarella contends that de-escalation zones (as a precursor to a peace agreement) do not honor their political or humanitarian purpose and only make the Syrian regime less likely to negotiate. There is also a particular emphasis on Russia committing to a “de-prioritization of the Middle Eastern Theater” (Cafarella) and the Turkey/SDF conflict reaching some sort of armistice.

Ms. Mona Yacoubian of the United States Institute for Peace and Dr. Bagherpour contend that greater political autonomy for Sunni minorities in Iraq and ultimately a significant devolution of power to governorates in Syria is a necessary condition for peace. Furthermore, Dr. Spencer Meredith III of National Defense University notes that the “SDF attaining a functional level of governance” is absolutely necessary for conflict resolution.5 Dr. Meredith also asserts that the US needs to advocate for strategic communication with Turkey on behalf of the SDF, whereas AMB Jeffrey takes this a step further and argues for a continued American military presence in Syria. AMB Dobbins and the RAND team similarly write of the usefulness of maintaining a US presence in counterbalancing Iranian in influence and providing leverage in negotiation over Syria’s longer-term future.

Socioeconomic Reconstruction

As political conventions for peace emerge, plans for the reconstruction of Syria must be correspondingly developed as well. Authors identified three mechanisms of socioeconomic advancement: micro-level community rehabilitation, reintegration, and humanitarian concerns. Both Ms. Yacoubian and the RAND team propose a bottom-up approach6 to development within and across communities to accompany an increase in decentralized governance. The RAND team and Dr. Ganor further articulate the importance of reintegrating refugees to forge economic activity and contribute to political participation in Syria. Ms. Cafarella notes the importance of creating mechanisms for DDR (disarmament, demobilization, and reintegration) and SSR (security sector reform) for former combatants.7 Basic humanitarian challenges are also of primary concern: specifically, the protection of minorities (e.g., Yazidis, Christians, etc.) (Bagherpour), the release of political prisoners and delivery of humanitarian aid (Cafarella), and the “continued monitoring of non-conventional material” (Ganor).

Contributors

Dr. Amir Bagherpour, giStrat; Ms. Jennifer Cafarella, Institute for the Study of War; Dr. Boaz Ganor, InterDisciplinary Center (Israel); Mr. Hassan Hassan, Tahrir Institute for Middle East Policy; Mr. Faysal Itani, Atlantic Council; Ambassador James Jeffrey, Washington Institute for Near East Policy; Dr. Spencer Meredith III, National Defense University; Alexander O’Donnell, giStrat; Dr. Nicholas O’Shaughnessy, University of London; Dr. Abdulaziz Sager, Gulf Research Center; Mr. Mubin Shaikh, Independent Analyst; Dr. Martin Styszynski, Adam Mickiewicz University; Ms. Mona Yacoubian, United States Institute of Peace

Comments