Question (R6.10): What can the U.S. and Coalition partners realistically do to enable Iraqi Security Forces (ISF) to combat a long-term ISIS insurgency? Recognizing the enormous resources the U.S. poured into the ISF from 2003 until 2011, only to see much of the force collapse in 2014, what can we do to avoid making the same mistakes when training the ISF?

Author | Editor: Canna, S. (NSI, Inc).

Executive Summary

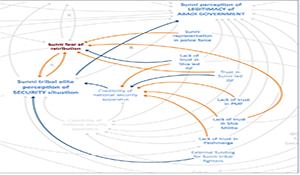

At the beginning of the Reach Back effort in 2016, Drs. Belinda Bragg and Sabrina Pagano from NSI Inc. created a qualitative loop diagram1 of security dynamics representing Kurdish, Shia, and Sunni populations in Iraq using NSI’s Stability Model (StaM).2 They found that security dynamics in the region were driven in large part by perceptions of social accord and governing legitimacy. These findings apply today to the study of why Iraqi Security Forces (ISF) failed in 2014, why they are strengthening today, and what pitfalls they may face in the future.

Iraq’s Sunni Arabs have voiced fears that, once areas of Iraq controlled by ISIL have been liberated, Kurdish and Shia Iraqis will seek to exact retribution against Sunni populations in these areas for the actions carried out by ISIL (Amnesty International, 2016; Fahim, 2016; Hauslohner & Cunningham, 2014; Rozen, 2016). “There are many barriers [to Sunni IDP’s WHAT CAN CENTCOM DO? Decreasing Sunni fear of retribu-on In Iraq there are a mul-tude of military and paramilitary groups and organiza-ons, with various levels of allegiance to and control by the central government. At present, they are at least loosely upeople accused—rightluynity or wrongly—of complicity and lack of coordination among local strongly iden-fied sectarian mili-a is likely to significantly reduce percep-ons of security and increase the likelihood of sectarian violence reemerging. authorities and security forces” (United States Institute of Peace Staff, 2016). (Bragg & Pagano, Specifically as this sec-on of the loop diagram below illustrates, the nature of the various military and paramilitary forces present in Iraq contributes significantly to Sunni fear of reprisals. Human SOCIAL Sunni sense of r i g h t2s a0b u1s e6s )

The loop diagram in Figure 1 suggests Sunni percep-on of equality R Sunni fear of retribu.on R Sunni tribal elite percep.on of SECURITY situa.on Sunni percep.on of LEGITIMACY of ABADI GOVERNMENT Lack of trust Corrup-on & patronage Sunni Ideological radicalism (New ISIL) Equal administra-on of rule of law & jus-ce GOVERNING CAPACITY Local / na.onal among Sunni, Shia, Kurd Sunni sense of to enhance Sunni perception of the aliena-on from Shia-led government’s legitimacy, Sunni government Cross-represectnaritaan ltanidon in the police become an Sunni representa-on in police force Lack of trust in Shia led ISF essential part of the professionalization disputes Sunni Sa-sfac-on with resource R Credibility of na-onal security apparatus of the ISF going forward (Bragg & quality ofmdistribu-on process & life Pagano, 2016). Failure to do so may turn Sunni populations, particularly in areas where ISF forces must operate in Ability / willingness of Sunni IDPs/refugees to return the fight against Daesh, against them (Hamasaeed, Kaltenthaler). However, as this type of analysis shows, there is also a “virtuous” loop where in crease Sunni perception of equality enhances perceptions of legitimacy, which enhances security, which ultimately enhances a sense of fair political representation (Bragg & Pagano, 2016). This loop highlights the centrality of political and social factors to the potential for stability and security in Iraq moving forward, which is also supported by Mr. Hamasaeed.

By updating the loop diagram to focus primarily on the role and function of the ISF, we can get beyond a list of the sources of failure and potential solutions to get at the heart of the problem: large segments of Iraq’s population (primarily Sunni Arabs and Kurds) do not trust the government, and by extension, the ISF. Where there is no trust, there can be no legitimacy.3 A government that protects the interests of Shia over Sunnis results in institutions, like the armed forces, that promulgate a negative feedback loop where the unwillingness of forces to protect Sunnis erodes Sunni trust in the government, resulting in the ISF being perceived as an illegitimate and ineffective force.

Experts note that ISF has made marked improvement in combating Da’esh over the last year (Liebl, Whiteside). They point to a new sense of nationalism among the citizens of Iraq and the ISF in the face of an adversary that has come to be seen as an existential threat. However, it begs the question of what will happen when the threat that has unified the country to some degree recedes. It also raises concern that while the population on average may experience rising nationalism, specific groups may not share in that experience, which can lead to unrest that affects the country. This is even more pertinent as ISF chases the remnants of Daesh fighters to rural, Sunni dominated areas with a military force led and comprised primarily of Shia personnel.

Figure 2 above provides a visual summary of the dynamics at play in the professionalization of the ISF. As mentioned above, the key drivers of ISF failure as identified by experts since 2003 include 1) lack of Sunni political representation, 2) weak national identity, 3) exclusionary policies within the ISF, and 4) negative perception of US policies and actions. This last point highlights the role the United States has played in undermining the success of ISF. Starting in 2003, the dissolution of the Iraqi army not only emboldened exclusionary policies that sidelined Sunni participation and trust in the armed forces, but also eroded US standing with Sunni populations in Iraq (Hamasaeed). Since then, inconsistent support (in terms of both training and funding) opened a vacuum, particularly after 2011, for Prime Minister Maliki to hollow out the officer corps to make it “coup proof” instead of effective and representative (Hamasaeed, Jeffrey, Kaltenthaler, Liebl, Sager, Whiteside).

The most frequent recommendation made by experts to ensure the ISF becomes a force able to combat a long-term Da’esh insurgency would be a US commitment to consistent, sustained engagement with ISF in the form of advice and, particularly, training. Figure 2 shows that a long-term US commitment consisting of a light footprint, training, and advice would help professionalize the army and build an institution built on strictures that would enhance the ISF’s standing as a legitimate, representative, rules-based organization. The population’s trust in the ISF is a necessary component to ensure that ISF can operate in and amongst Sunni populations where Daesh is likely to hide.

The threat and subsequent successful campaign against Daesh in Iraq has presented an opportunity for the country to build on a nascent sense of nationalism to professionalize and institutionalize Iraqi Security Forces as a legitimate guarantor of security for the people of Iraq. However, this transformation requires the consistent, sustained commitment of the US and Coalition partners to provide training and advice to Iraqi forces. As we saw in 2011, disengagement creates an opportunity for sectarian policies, fears, and grievances to emerge that would quickly erode any trust Sunni population might have for the ISF, making Iraq’s efforts to combat Daesh ineffective at best and counterproductive at worst.

The stability model constructed in 2016 tells us that “attempting to isolate security engagement efforts from the broader political and social forces at play in Iraq is futile…Security is intrinsically linked to perceptions of governing legitimacy and the dynamics of ethno-sectarian relations. Thus, whatever diplomatic, informational, military and economic levers the U.S. employs in Iraq, attention must be paid to the influence they might have on both of these factors.” (Bragg & Pagano, 2016). As happened in 2011, if OIR is declared a success and the US pulls out, ISF risks becoming once again into the tool of Shia sectarian forces. In the event that a Maliki-aligned, pro-Iranian government is elected in May, Dr. Kaltenthaler concludes, “it is better to be forced to leave Iraq rather than withdraw before the long term mission of stabilizing Iraq is complete.”

In closing, we will leave you with a disruptive thought presented by Dr. Craig Whiteside of the Naval Postgraduate School: it is the local police, not the army that has the primary role in combating terrorism. He argues that army units should be employed to prevent Islamic State fighters from openly grabbing territory and having access to the population, but it is the local police that are best poised to adjudicate relations between the population and insurgent groups.

Contributors

Mr. Sarhang Hamasaeed, United States Institute of Peace; Ambassador James Jeffrey, Washington Institute for Near East Policy; Dr. Karl Kaltenthaler, University of Akron & Case Western Reserve University; Dr. Michael Knights, Washington Institute for Near East Policy; Vernie Liebl, ProSol Associates & Center for Advanced Operational Cultural Learning, US Marine Corps University; Dr. Spencer Meredith III, National Defense University; Dr. Nicholas O’Shaughnessy, London University (UK); Dr. Abdulaziz Sager, Gulf Research Council; Mubin Shaikh, Indepdendent Analyst; Anonymous Smith; Dr. Craig Whiteside, Naval Postgraduate School