US Retain Stability in Post-Kurdish Referendum Iraq

Question (R6.8): What is the role of the United States and coalition partners in maintaining stability as Iran, Iraq, Turkey, as other groups grapple with the Iraqi Kurdish independence referendum?

Authors | Editors: Aviles, W. (NSI, Inc.)

Overview

Since the controversial September referendum for Iraqi Kurdish independence, the political stability of the Kurdistan Regional Government (KRG) and its relationship with the Iraqi government has been in crisis mode. The political uncertainty of the KRG has been clouded by the de jure resignation of President Masoud Barzani, an increase in violence and protests, and mounting economic woes. The precarious political balance between Erbil and Baghdad is not only subject to the tensions of internal Kurdish affairs, but also by the complex interests of regional and sub-state actors and the looming Iraqi parliamentary elections in May. Contributors to this response largely agree that actual Kurdish independence is very unlikely in the short-medium term and, moreover, that maintaining the territorial unity of Iraq and Kurdistan is critical to security in the region. However, contributors differ slightly on how to approach facilitating and maintaining stability in Iraq and how to balance competing interests from the KRG, sub-state actors in Iraq, Iran, Turkey, and the international community.

Referendum for Independence

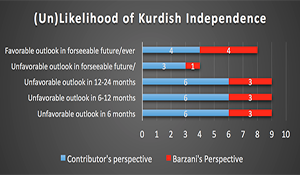

The independence referendum continues to be both a source and symptom of tension between Erbil and Baghdad. Furthermore, opposition from regional and international actors has resulted in significant setbacks for the KRG. Several experts cite the referendum as the catalyst for the territorial losses, decay of the ruling political class of the KRG, and the punitive measures the KRG has received from the Baghdad, Ankara, and Tehran—all of which makes independence more unlikely (Gulmohamad, Liebl). Concurrent with expert consensus from an earlier reachback report,1 Dr. Muhanad Seloom of the University of Exeter (UK) contends that the referendum was a gambit of political posturing intended to “maximize the KRG’s political and economic gains,” rather than an honest bid for independence. Experts are less decided on the long-term possibility of an independent Iraqi Kurdistan as can be seen in Table 1.2 Since the referendum is responsible for a large portion of the KRG’s current political strife, Dr. Gulmohamad of University of Sheffield (UK) argues that the referendum will be utilized as bargaining chip as a “long-term strategy if/when the relationship with Baghdad gets worse or fails to improve.” As Erbil struggles to consolidate resources and political unity, the fallout of the referendum continues to expose and personify the underlying tensions between the KRG and the Iraqi government.

Sources of Instability

The movement for Kurdish independence in Iraq has a contentious history that has overlapped into the many conflicts and turmoil of Iraqi politics on both a national and regional level.3 It is therefore not surprising that mechanisms of instability can be attributed beyond the political implications of the September referendum. Experts discuss three interdependent sources of controversy between the KRG and other political elements in Iraq, namely economic revenue, political representation/power, and territorial governance. Iraqi Security Forces (ISF) (with militia support of the Popular Mobilization Forces) have mounted several successful campaigns against Daesh that have reinvigorated federal authority, which resulted in the eventual reclamation of the Kirkuk governorate and other disputed territories from the Peshmerga (Gulmohamad, Liebl). These areas are coveted by both Erbil and Baghdad for their petroleum resources and smuggling routes, which both entities heavily rely on for revenue. These territorial losses ran concurrent with the disunity and fractionalization of the KRG political elite following the referendum and have left the KRG in a weak position to negotiate for a share of the resources found in the region. Baghdad’s reassertion of authority, coupled with current weakness of the KRG cited by several experts, present opportunities for negotiation and to resolve these crises (Gulmohamad, Liebl). Dr. Muhanad Seloom of the University of Exeter (UK) contends that these conflicts between Erbil and Baghdad are not new and, moreover, that “the secret behind the agreements and concessions between Baghdad and the KRG has been the elections and formations of government.” Another scholar argues that such an engagement cannot occur under the current Kurdistan Democratic Party (KDP) and Patriotic Union of Kurdistan (PUK) hegemony due to their personal financial interests. This is critical as a meaningful reconciliation between Erbil and Baghdad hinges on a foundational overhaul of the KRG leadership.

What Can the US Do?

A majority4 of contributors argue that the US is best positioned to play the role of mediator and facilitate negotiations5 between Erbil and Baghdad, but suggest alternate methods of diplomacy. Dr. Ofra Bengio of Tel Aviv University emphasizes the KRG as the most consistent ally to the US and that Washington should demonstrate strong support for the KRG over the Iraqi government and other Shia and Turkish interests. Dr. Abdulaziz Sager of the Gulf Research Center stresses the need for the US to maintain the current sovereign integrity of Iraq and that “anything else opens a Pandora’s box with incalculable results and consequences.” AMB James Jeffrey and Dr. Michael Knights from the Washington Institute for Near East Policy continue this calculus but recognize the importance of maintaining the KRG as a pro-Western influence element within Iraq. They suggest that Erbil-Baghdad disputes endanger this paradigm. Dr. Knights goes on to clarify that “we are not on Baghdad or Erbil’s side, we’re on the [Iraqi] constitution’s side” and so the US has a strong interest in facilitating legal resolutions to all political disputes. Dr. Nicholas O’Shaughnessy of University of London suggests military aid to both the KRG and Baghdad could be used as a useful negotiating asset in mediation. Interests of Iran and Turkey Both Tehran and Ankara aligned with Baghdad on sanctions against the KRG following the referendum and, for the most part, share an interest in preserving the territorial sovereignty of Iraq (Gulmohamad, Jeffrey, Seloom). Turkey has a vested interest in the petroleum production of the Iraqi Kurdistan Region (Jeffrey), Iran seeks to preserve their smuggling/patronage networks (Seloom), and both entities want to ensure the KRG is free of adversarial (e.g., Kurdistan Workers’ Party [PKK] and anti-Iran Sunni) influence. While contributors note the importance of perpetuating the US as the primary ally of the KRG, experts favor cooperation between the KRG with Ankara over Tehran (Jeffrey, Knights). Such cooperation is framed in the scenario of Baghdad becoming increasingly entangled into the yoke of Iran and by granting Ankara stakeholder influence with the KRG, Erbil could better balance an Iranian controlled Baghdad. Despite the interests of Iran and Turkey, contributors have not stressed the importance of their influence on Erbil-Baghdad dynamics but again, emphasize the role of the US in forging stability in Iraq.

Contributors

Dr. Ofra Bengio, Tel Aviv University (Israel); Dr. Zana Gulmohamad, University of Sheffield (UK); Ambassador James Jeffrey, Washington Institute for Near East Policy; Dr. Michael Knights, Washington Institute for Near East Policy; Mr. Vern Liebl, Center for Advanced Operational Cultural Learning (CAOCL), Marine Corps University; Dr. Nicholas O’Shaughnessy, University of London (UK); Dr. Abdulaziz Sager, Gulf Research Center; Dr. Muhanad Seloom, University of Exeter (UK); Mr. Mubin Shaikh, Independent.